- Dates2 September 2017 - 4 November 2017

- Artists

by Phong Bui, Brooklyn Rail*

On the occasion of Joanne Greenbaum’s second one-person exhibition at Rachel Uffner Gallery (May 20 – July 1, 2016), which features both recent paintings and sculptures, Rail publisher Phong Bui paid a visit to the artist’s Tribeca studio to discuss her life and work just a day before the works were transported to the gallery for exhibition.

Phong Bui (Rail): I thought it would be good if we would pick up where we left off last time.

Joanne Greenbaum: I remember when you were here in my studio last winter, we talked about Elizabeth Murray, who was my teacher at Bard College.

Rail: Exactly! How remarkably she was able to embrace her particular stubborn and eccentric brand of speed of execution and unusual paint handling techniques, which were all sensible aspects of how she made shapes, forms, and images on her idiosyncratically shaped canvases. Her work and yours are vastly different, yet there is a similar reference to urban energy packed into a compressed space, despite an apparent subject matter of still life and domestic interiors.

Greenbaum: I shared that interest in still life, but whereas her paintings contain visible domestic interiors—tables, cups, and so forth—my work tends to detail the architectural space of interiors, like stairways, scaffolding, and other ambiguous geometric structures. And I don’t care about the grid. But there are things in architecture or urbanity that you can play with.

Rail: I meant the pace of the energy generating from the work. In other words, both your and Elizabeth’s paintings couldn’t be made outside of New York City.

Greenbaum: One thing I can say about myself is that I don’t ever stay still. It doesn’t mean I’m always moving forward, I could be moving back. Sometimes I want to go back to something I did earlier and then bring it forward. But the paintings are a sort of exploration. I don’t really like that word because I don’t think about it like that at all, but somehow I think it’s more about being true to whatever your energy is at that moment and tapping into it as a source, which essentially makes the painting.

Rail: What about an unconscious level of predictability that becomes habitual without you necessarily noticing it?

Greenbaum: I won’t work. I’ll stop because I get bored. I don’t want to know where I am or where I’m going in a painting. I have no idea and I need to keep it open and alive for that to happen. And it’s not always joyful, sometimes it’s very hard. Being something of a workaholic myself, I need to keep that channel fresh in a painting so that I can feel I’m keeping pace with the journey. If it’s going somewhere I’ve been before, I won’t go on.

Rail: And change gears—

Greenbaum: —by making a drawing, a watercolor, or sculpture! One important thing I learned from Elizabeth was love and respect for art materials. I used to talk to her about different things I found in art supply stores, and I thought I was too much of a materials nerd. I admit that I love being in those stores. And Elizabeth always made me feel good by saying, “That’s what artists do.” I think it’s really important to get the right paper for the type of pencil that you’re using, for example. Nowadays, I use all kinds of new materials, Flashe paint, oil crayon, Magic Marker, acrylic and so on, partly because I want the paintings to be very alive with different temperatures.

Rail: And space.

Greenbaum: Yes. And I like to think of different stages of the painting as some sort of performance with the materials.

Rail: That makes sense. I mentioned the undeniable urban energy and how it affects the way artists, being sensitive to their environment, make their work. Mondrian is a good example. He started out as a landscape painter, in the Dutch Impressionist manner of the Hague School, before ending up making drastic changes after developing a deep interest in theosophy, and H. P. Blavatsky, and the whole issue of spirituality in art—

Greenbaum: —where he thought of trees as verticals and landscapes as horizontals, among other things.

Rail: Right, but between 1911 and 1914 when he was in Paris—Mondrian was nine years older than Picasso—it was remarkable that he allowed a younger painter to influence him. It was through Cubism that he arrived at his mature works, which refer to the opposite of naturalism—artificial, architectural structures—through which some thought Mondrian brought Cubism to its logical conclusion. When he came to New York in 1940, he even covered the windows in his studio. The results were works like Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942 – 43) and Victory Boogie Woogie (1942 – 44), which could have only been made in New York. Wouldn’t that be cool, to make a show of painters whose work changed in response to their mental and bodily experience of New York City’s energy, which would include Mondrian and Elizabeth Murray, among others? Mondrian is calmly sitting on a bench, Elizabeth is leisurely walking, and you are frantically running. The pace is interesting. I don’t know whether it’s conscious or subconscious, but it’s definitely very visible in the way the work appears.

Greenbaum: I don’t think it’s that conscious. Though lately I’ve gotten so over sensitive to noise and construction due to the neighborhood’s inflated popularity. I also have a house out on the North Fork, Long Island.

Rail: Since when?

Greenbaum: A little under two years. Spending time there, going back and forth, I feel an element of nature. It may be very subtle, but I feel it’s there. It’s also nice being away from the studio for two or three days a week—sometimes more, sometimes less.

Rail: You get recharged.

Greenbaum: You also get distance. I come back with a fresh eye. I’m not in that forced mindset, which is very important to me because my work changes all the time, from one show to the next, one body of work to the next. I’ve never made the same type of thing. I’m not that kind of artist. I have certainly have never branded myself, that’s for sure.

Rail: Let’s talk about your drawing, because I feel that it plays a major role in your painting and sculpture. When I look at the way the lines function, I notice in each drawing they often have no more than two characters of line. One seems to be swirly, in billowing spiral formations, while the other tends to conform to quasi-geometric structures. Sometimes the distinctions between them are very clear, sometimes not. It all depends how each line is allowed to build up. Either way, the lines are consistent in their pace and insanely free in their repetition. It’s like trying to make a structure out of a group of live tornadoes—

it’s almost impossible. I can understand why some of your critics are puzzled about what you do. Roberta Smith referred to your painting as “nicely abrasive” and “inharmonious in color.” Ken Johnson thought of them as “dances between opposite personalities.” There’s a kind of nervous impulsiveness that makes viewers feel as though you are working out some kind of inner conflict.

Greenbaum: I think that’s true. I think, on the one hand there are two types of drawing: One is almost like analytical cubism, where I’m trying to figure out structure, figure out context. I need that scaffolding to work on. The other kind of drawing is almost like a physical negation of that. There’s this bodily wiping out. But I think it’s possible to do both simultaneously, at least for me. You don’t have to be one or the other, you can be both. You can be structured and loose at the same time. You can be serene and angry at the same time. Those things all work together, it’s not like you’re one or you’re the other. I think my paintings and drawings really speak to that without being schizophrenic.

Rail: And there is an inherent order without calling it order as such.

Greenbaum: Yes, absolutely.

Rail: Take the biggest untitled painting you’ve made, for example, which measures 145 × 135 inches.

Greenbaum: I’ve never worked that big before.

Rail: Can you share with us how you begin with such a large format? What gets painted first?

Greenbaum: With this particular one I started with a large, broken shape that functions like a structure. I started with blue—very slowly. Then, at some point, I worked with the palette knife to lay on different colors while making the drawing right on the surface, simultaneously. At the end of a painting the whole thing somehow pulls together. Also, the way I use paint now with a palette knife is a kind of drawing which functions like the skeleton of the painting. And the physical layering of paint on the surface makes the painting feel like it’s a physical object.

Rail: You use that same technique in other paintings as a way to interrupt or rupture the harmony of the structure.

Greenbaum: Sometimes I’ll look at a painting, almost at the end, and say to myself, “What’s working here?”—whether the painting is too rigid or too pretty—“that I need to interrupt or ruin?”

Rail: Is the ultra-marine blue in oil?

Greenbaum: Yes, it’s ultra-marine, but in Flashe paint. I’m sort of embarrassed to say that the blue is so Matisse-like that I feel uncool about it.

Rail: You should feel cool about your blue because Matisse was once asked why he used so much black in his paintings and responded that it was to cool down the blue. It’s interesting because blue is the hottest part of a flame, not the red.

Greenbaum: That’s an interesting fact. Sometimes I have to hold myself back from using black because everything looks good with black. It’s very seductive.

Rail: In the interview with Jeremy [Sigler] you talked about how important the MoMA was to you as a kid.

Greenbaum: Because I was such a miserable child, and an awkward teenager. I grew up in Westchester, in the suburbs of New York City, so it was easy to get to the city. The MoMA was my only savior.

Rail: It was your equivalent of the mall.

Greenbaum: Yes! Everyone went to malls. I went to MoMA. I grew up there. Every Saturday, from the time I was twelve to the time I went to Bard College, I would go and sit at MoMA and draw in my little notebook. I don’t even know what I was doing there, maybe I wasn’t even looking, but something just sort of seeped in that became my backbone. Maybe it is the same for a lot of people. I think for many people it’s television or films or something else from their childhood that they internalize. I think for me it was Cubism and Surrealism and all of those things. Picasso and Miró, I think about Miró sometimes even more than Picasso. There’s part of me that’s still fighting that as well, because I certainly don’t want to be labeled. It’s important for me not to be labeled.

Rail: You and Mary Heilmann both share that kind of resistance.

Greenbaum: Don’t put me with a group of artists, because I don’t belong there. I’ve always been allergic to groups. When I was coming up in New York as a young artist I was never really part of a network of artists.

Rail: You moved to New York immediately after graduating from Bard in ’75.

Greenbaum: Yes, as soon as I moved here I started working jobs. I always had to work. I just lived my life. I had a few good friends but I was very isolated for the most part. And I wasn’t part of the East Village thing that happened in the early ’80s. I was there, I went to galleries, I went to shows, I tried to show my work, but I was very peripheral. I didn’t participate. I think I feared participation. I had a lot of social anxiety.

Rail: We all have to overcome our old habits in order to grow.

Greenbaum: That was what I did between 1986 and ’92 when I basically threw everything out from my past. I was so frustrated. I wanted to show my work, I wanted to participate but I just couldn’t. I didn’t have the facilities or connections. So I really just retreated and did some soul-searching with my work and realized that I needed to just start from scratch. When I first started showing I made these really simple paintings on white ground by not using a brush, just using stains, pours, which was inspired by a big Morris Louis show at MoMA in 1986. It was a way out from the thick paint, from the many layers that built up, creating this claustrophobic feeling.

Rail: They were labor-intensive and had no air.

Greenbaum: Yes, and I threw them all away. Meanwhile, I was making these very attractive paintings that were based on the concept of lightness and transparency, though they eventually came to a dead end. I felt if I kept going in that direction, I would be moving towards Minimalism or total idea-based painting, which just wasn’t for me. There was no room for my personality. I really felt the need to put my personality back in the paintings.

Rail: Was that the time you began to incorporate drawing, which I see as the obsessive part of personality, and painting, which I see as the formal part of your rational thought?

Greenbaum: The two were separate for a long time. But yes, when I put them together as one activity, that’s when I actually began showing my work. First I was invited to be in some group shows in the early ’90s and then I had my first solo show with Arena Gallery in 1996, then at D’Amelio Terras in 1997. That was the moment when the drawing and painting started playing around together.

Rail: Instead of arguing with each other.

Greenbaum: Right.

Rail: Like in Borges’s famous prose poem, Borges and I, which has no plot whatsoever. The narrator, who can be identified as Borges though he remains unnamed, seems to know Borges the writer in the same way he knows the streets and the architecture of Buenos Aires. What is so interesting about this perplexing, ambiguous story is that it explores the concept of identity and the differences between the private and the public persona, between Borges the writer and Borges the person. It’s like going through a labyrinth—which is unlike a map (I know you refute it when viewers make that comparison to your work)—you might end up in the same place without understanding how you got there. In other words, to move through a labyrinth is to explore a new or unknown space.

Greenbaum: That’s how I feel every time I approach each painting.

Rail: So in this regard, painting and drawing, and Joanne the hermetic, reclusive person and Joanne the driven, ambitious painter, are only separated by a tiny strand of hair.

Greenbaum: It’s like the painter saying to the person, “You better get it together! Get yourself together, girl. You got to get out there. Show your work. That’s the only way to make really good paintings because your personality is not going to get you there.” You’re not going to get yourself there when you’re shy, or have anxiety in groups. You can’t just do your work, make great paintings, and expect to get where you want to go.

Rail: And that gave you confidence?

Greenbaum: Yes, that gave me confidence to participate in life a little bit more. It took me a really long time.

Rail: Do you have any particular feelings about the sense of scale as opposed to size, especially in regard to your off-square format, which can be seen as a stable configuration, and in regard to this big painting you’ve just painted, which is the biggest you’ve painted up to date?

Greenbaum: I feel very free making big and medium-sized paintings even though they require much more physical stamina. Running up and down a ladder makes you feel as though you’re moving in the space instead of standing before it. When I work this big, I can incorporate all of the things I do, as in a big novel, whereas smaller paintings are more about little scenes in a novella, in a sense.

Rail: That’s a good comparison. Do you think starting to make ceramic sculptures in 2003 changed your thinking and feeling about form and color?

Greenbaum: Yes, because of the nature of clay—soft, loose, malleable—which to me functions like three-dimensional drawing. There is this reverie that I get when I draw, and I transferred that into the sculpture. What inspired me to make sculpture was that I felt like my paintings were fictional sculptures. I think that working with clay has loosened up the line in my drawing. The drawing sometimes becomes a silhouette of a sculpture.

Rail: Do you think that your sense of color has changed since you started making sculptures?

Greenbaum: I think so, partly because I’m not that interested in glazing, which is a major part of ceramics as a medium. For me, I basically make the pieces, fire them, and bring them back to the studio and use my own materials to color them. So, in a way they’re like three-dimensional paintings. I essentially treat them as another surface to paint on.

Rail: What do you do when things don’t come together in a drawing, a painting, or a sculpture?

Greenbaum: When I make a work, the goal isn’t resolution, it’s more irresolution, even though you can say some are probably more resolved than others. For those that don’t come together, I just let them be. I don’t really believe in forcing anything in my work.

Rail: When did you really develop that confidence to allow things to argue among themselves in the work?

Greenbaum: I think showing my work gradually gave me confidence. Over the years of showing in different parts of the States and abroad, I’ve learned that I may not be a confident person, but I’m a confident artist.

Rail: Who says Joanne the artist and Joanne the person have to be reconciled?

Greenbaum: They’re still arguing, and it will probably always be like that.

*read original Brooklyn Rail article, 3 June 2016

by John Yau, Hyperallergic*

Joanne Greenbaum began making tiny sculptures out of Sculpey in 2003. The following year she enrolled in a ceramics class at Greenwich House, a non-profit community arts school in Manhattan’s West Village. The class gave her access to materials and a kiln, but she didn’t want to learn the right way to make ceramics, and wasn’t interested in making vessels. I can imagine the teacher and fellow students in her adult education class being bewildered by the non-functional, abstract pieces she made.

Most of the early ceramics were relatively small, able to fit inside your hand. Now, nearly fifteen years after she enrolled in the class, Greenbaum has made larger, multipart sculptures out of porcelain, air-dried clay, and cast aluminum that liberate an odd structural beauty from folded, twisted, looping and slab-like forms. Most of the porcelain and clay sculptures are painted and drawn on in unexpected ways. A group of recent sculptures and paintings (all made in 2015-16) –– including what I believe is the largest painting the artist has made to date –– can be seen in her first-rate exhibition, Joanne Greenbaum: New Paintings and Sculptures at Rachel Uffner (May 20 – July 1, 2016).

Greenbaum’s interest in diverse materials as well as her resistance to learning the right way to use them are central to her work. I suspect that the artist made “Untitled” (2016), to fit on the far wall of the gallery’s first floor, which has high ceilings and a skylight. Done in oil, acrylic, Flashe, ink, oil crayon and marker on canvas, the painting measures 145 x 135 inches, and is the largest work of hers I have seen exhibited in New York. An incremental artist who keeps finding ways to add something unexpected, in “Untitled,” Greenbaum lays down ultramarine cutout shapes extending inward from all four sides of the painting. The deep blue shapes – with white (or unpainted) lines cutting through them – become something to work with, against, and around. The shapes evoke comparison to jigsaw puzzle parts and irregularly cut pieces of scrap metal.

There is also a large, pink, peanut-shaped cloud in oil crayon occupied by two small red irregular rectangles containing a black shape in their center. This pink, vertically oriented, semi-transparent, cell-like structure is located in the middle of the painting, near the top, setting in motion a dialogue with what’s around it. There are also yellow bands and shapes, networks of meandering pink and green lines, clusters of variously colored, feathery brushstrokes, and a smattering of dot-like shapes.

The white ground of “Untitled” is close enough to the gallery’s white wall that I wondered what it would be like if Greenbaum started making paintings on the wall. “Untitled” is like a party full of well-dressed adults, scruffy adolescents, lounge lizards and children in fluffy pink pajamas, all talking brilliantly at the same time. By spanning the hierarchy that distinguishes the sophisticated brushstroke from the child-like scribble, the artist dissolves the borders separating one kind of mark making from another. This is what I find so refreshing about her work. She is not trying to pass as an outsider or graffiti artist. Rather, she is bringing all these possibilities and mark making materials into play. She has opened up painting’s doors and invited everyone to come in.

And, as with any party full of brilliant conversationalists, there is always the one person who says something that gets everyone’s attention. Greenbaum is a tightrope walker crossing over pandemonium; she courts chaos but never descends into it. In another painting called “Untitled” (2016), which is in the upstairs gallery, a swarm of colored brushstrokes moves into and over colored flat shapes, like a horde of hungry beetles. In a number of paintings both upstairs and downstairs there are a row of evenly spaced drips running down the painting’s surface, like a beaded curtain.

Greenbaum’s genius resides in her ability to bring all kinds of binaries into play, without making them look contrived, collaged or quotational. Everything plays off what’s around it. If you can imagine one half of a dancing duo doing the waltz, and the other doing the rumba, and the two of them twisting around each other like friendly snakes, then you get an idea of what Greenbaum can do in a painting.

Whereas her first ceramic sculptures might have seemed less interesting than the paintings she was doing at the same time, the recent one constitute a distinct body of work within her expanding oeuvre. While they are decidedly not vessel, some of them resemble a vintage planter trying to escape its identity. Greenbaum further complicates this by applying gouache, or ink, or marker, or crayon – usually only one – in ways that don’t correspond to the smooth folds, irregular strips, rectangular slabs, and jagged forms that she has put together. As with the paintings, Greenbaum collides things together – in this case, form and color – attaining a mysteriously melodious cacophony.

In many of Greenbaum’s works, one sees the seeds of something that could become either a style or a formula. There are characteristics that seem uniquely hers – the row of evenly spaced drips, or the use of paint and marker in the same composition. However, as the paintings and sculptures in this exhibition make evident, she is too restless and questioning to settle into a set of predictable moves. Moreover, she repeatedly proves that she will do anything to keep the party going, including interrupting or covering parts of it over. Of course, this is why parties can be so interesting, so full of life and anarchic energy: they are not well-oiled machines. Her unruliness connects her to the Abstract Expressionists, but, in her case, there isn’t any trace of nostalgia or melancholy. I wish I could say that I am amazed that no museum in America has given her an exhibition.

*read original Hyperallergic article, 19 June 2016

by Roberta Smith, New York Times*

Joanne Greenbaum is operating at full capacity in her latest show at Rachel Uffner, confirming that she would have been a strong addition to the Museum of Modern Art’s recent painting survey. At the same time, she is also settling decisively into threedimensions.

Her latest canvases give new meaning to Harold Rosenberg’s characterization of Abstraction Expressionist painting as “an arena in which to act” by infusing it with high-low humor instead of macho angst. Up close, circuitries of exuberant lines and scrawls in pencil, crayon and marker course in and out of precarious edifices of high-wattage color that from a distance provide a semblance of order — but barely. The roles are not fixed. Ms. Greenbaum uses paint in graphic ways, dripping it in parallel lines, in some paintings, for example, creating fringelike areas or bead-curtain backgrounds. And her drawing often builds painterly steam; in the show’s largest painting, a big cloud of pink crayon rises amid a network of electric blue shapes thatevoke an agitated Matisse cutout.

In the upstairs gallery, Ms. Greenbaum takes her improvisations into actual space with tabletop sculptures in ceramic and cast aluminum that suggest misshapen architectural models or vases. The eight porcelain pieces, unglazed but worked by hand with ink and gouache, are especially strong. Color is smeared, loosely geometricor poured. One standout is a furl of delicate cabbagelike leaves dripped with red and yellow ink after being covered with fine red scribbles. Ms. Greenbaum’s sculptures aim high and are nearly on equal footing with her paintings.

*read original New York Times article, 3 June 2016

-

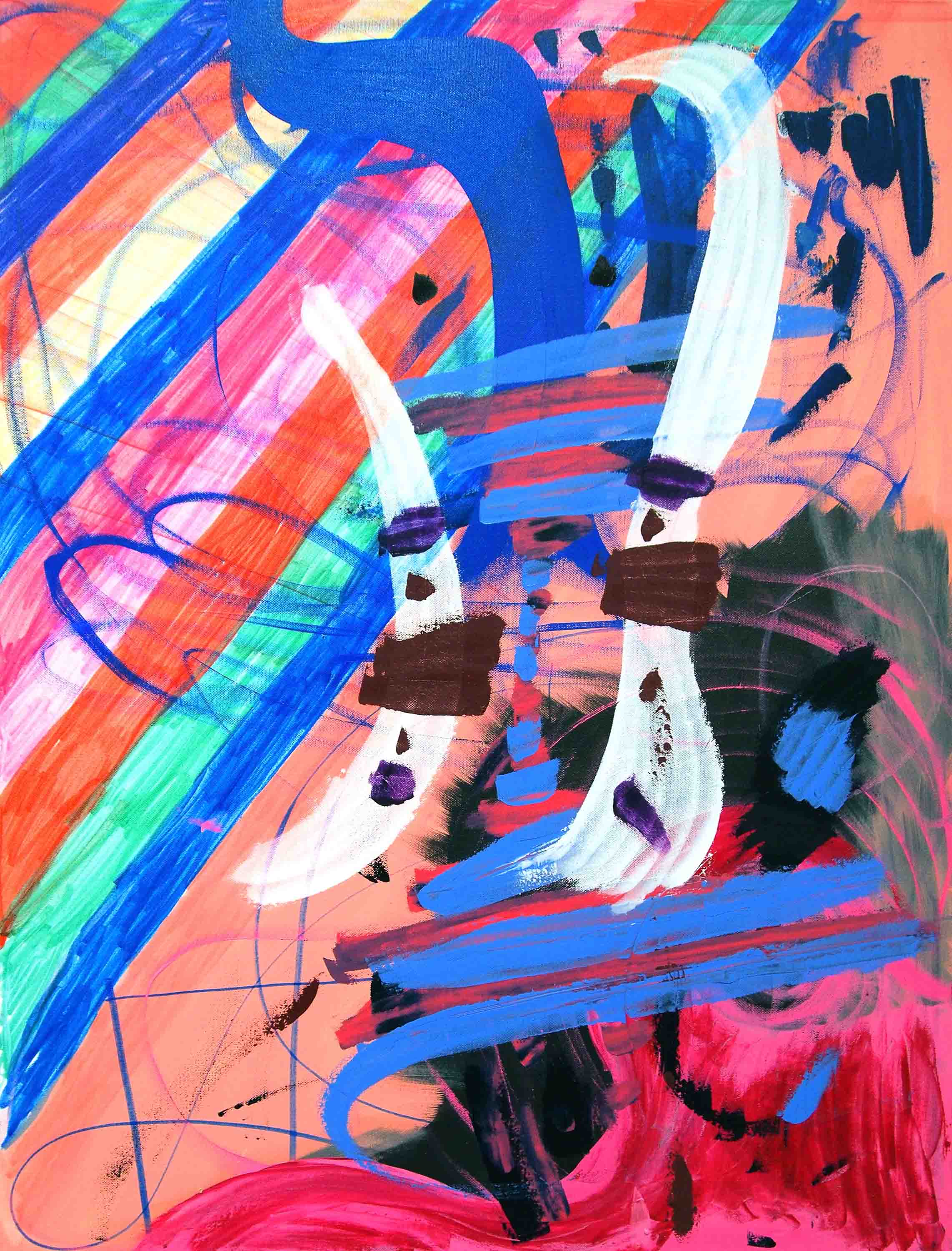

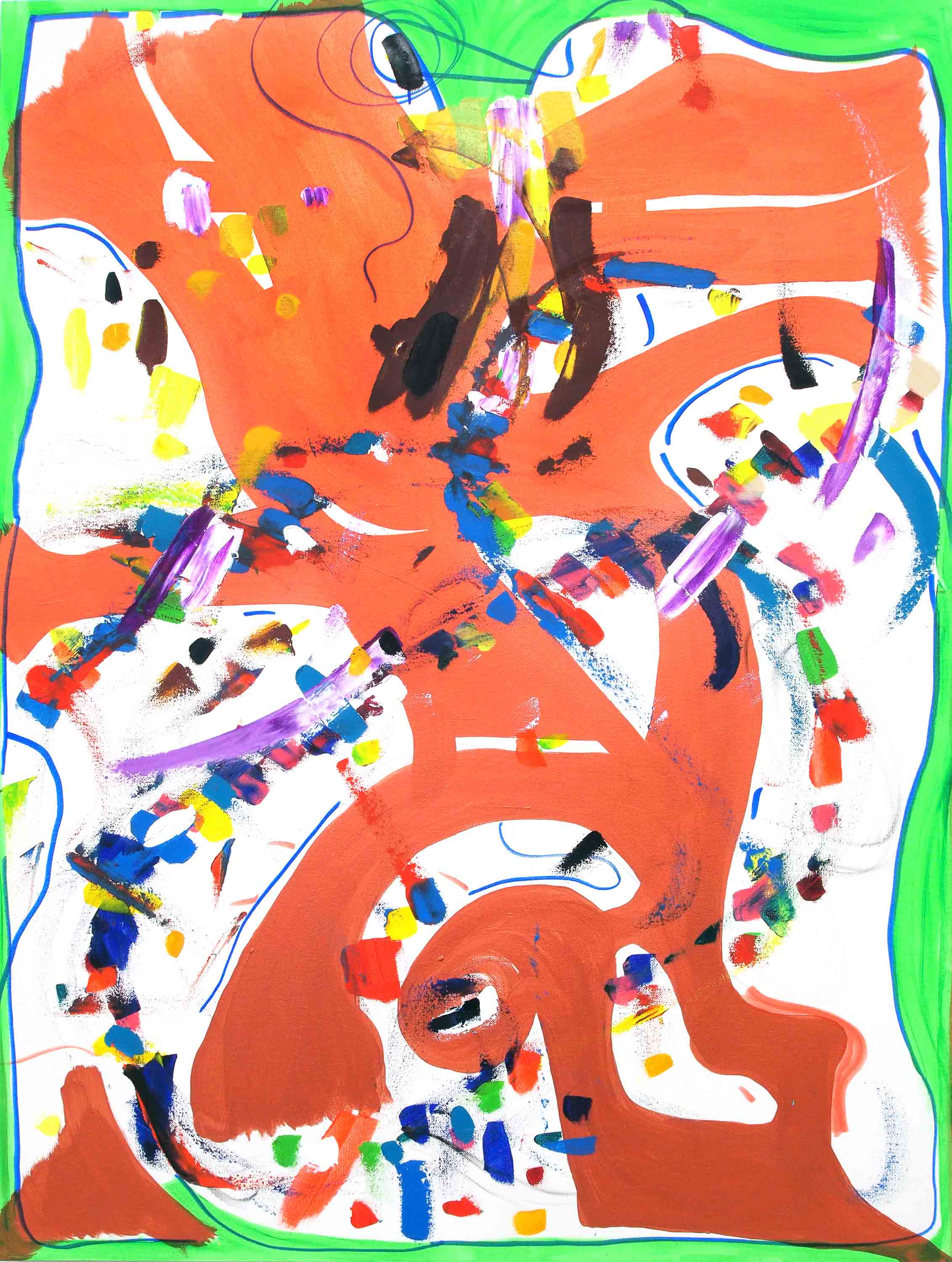

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm

-

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm

-

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil and acrylic on canvas

101,6 x 76,2 cm

40 x 30 inches -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2017Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

40 x 30 inches / 101,6 x 76,2 cm

-

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2014Oil, ink, marker, acrylic on canvas

78,7 x 70,9 inches / 200 x 180 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2014Oil, marker, acrylic on canvas

78,7 x 70,9 inches / 200 x 180 cm -

Untitled

Joanne Greenbaum2008Watercolor and gouache on indian paper

30 x 22,5 inches / 76,2 x 57,2 cm