Lin May Saeed

Lulu, Mexico City, Mexico

In the aftermath of Mexico City’s deadly 19 September earthquake, Frida, an endearing rescue labrador, became a beacon of hope for many locals. Anthropomorphized with goggles and all-terrain boots, Frida found dozens of victims trapped in the rubble, earning public adulation in the way only non-human companions do. Sometimes, tragic circumstances call for species interdependence, a theme that courses through Lin May Saeed’s alluring exhibition at Lulu.

Saeed’s charcoal Mural (all works 2017), commissioned for Lulu’s front space, has a formal naïveté redolent of paintings by Henri Rousseau. It depicts an imaginative ecosystem: a kneeling beekeeper and a few members of her swarm join a bull that balances an ostrich egg on its tail, a big cat and a bipedal hybrid with cloven hooves. They seem to peacefully coexist in the mural’s foreground, huddled together on a path of linear perspective, under spotlights that beam scribbled rays. There is an implausibility to this gathering: for what reasons do a human, animals, and a being-in-between commune? The mural’s harmonious procession seems almost biblical, somehow before and after our time.

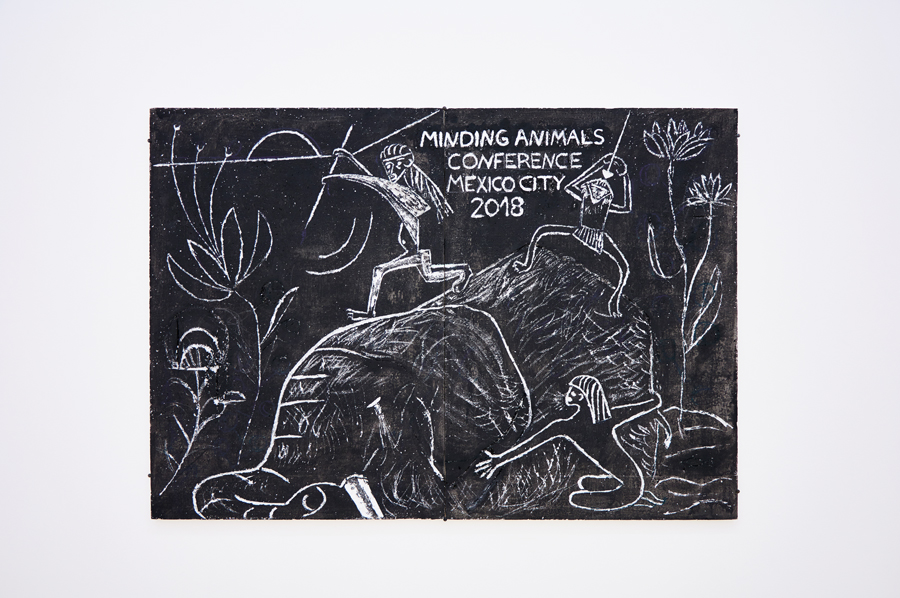

Charm abounds in this show, though Saeed addresses brutal subjects. In Mammoth relief, two humans with spears butcher a fresh elephantine kill, while a third seems to embrace the dead creature, a dramatic scene scratched into relief on a polystyrene tablet coated with black paint. The words ‘Minding Animals Conference Mexico City 2018’ hover over the tragic tableau, a reference to an activist and academic group that seeks to establish legal protections for non-humans, a cause that Saeed shares. Eschewing the surrealist intensity of Alexis Rockman, for example, Saeed’s style softens the drama at hand, and encourages a sense of empathy between her non-human subjects and very human viewers. Installed in front of Mammoth relief, Djamil sculpture – small Bactrian camel carved from polystyrene, coated with chunky white gypsum and daubed with brown paint – trots atop a pedestal crowned with newspaper, folded to reveal an image of faithful Frida. Saeed ascribes dignity to humble materials and noble animals alike.

The use of synthetic matter, light and buoyant particulate that so easily crumbles and chips, poetically gestures toward the precarity of natural ecosystems. In Lulu’s back gallery, floors painted the pale colour of silica sand lend the work a beachy touch. A styrofoam seahorse floats, fragile and elegant against a background of desert beige and aquamarine (Teneen Albaher Relief III). Can this creature survive the anthropocene? We might wonder the same about Saeed’s Lobster, sculpted from copper tubing and tarnished black with welding tacks, which sits atop copies of an essay about animal freedom by writer and theorist Melanie Bujok, stacked up to form a low plinth. We look down on this crustacean, but Bujok demands us to elevate its status: in her essay, she argues that animals should be free from murder and exploitation. Back on the stormy surface of the sea, we witness the violent ways of humans once again: in Saeed’s Djamil Relief, another painted polystyrene low-relief, an ominous ship helmed by humans fires a volley of arrows at another vessel, captained by a lone camel. We need animals more than they need us – though we may not realize it until it’s too late.