Lin May Saeed’s Slow Burn

Imagine our distant decedents encountering the work of Lin May Saeed some, I don’t know, several hundred thousand years from now. They might initially be perplexed by its use of Styrofoam (a material, it just so happens, that will have survived bronze and marble by millennia, miraculously intact), but after a little investigation they will realize that it was precisely our love of this material, fashioned from petroleum, that was responsible for our collective demise and extinction.

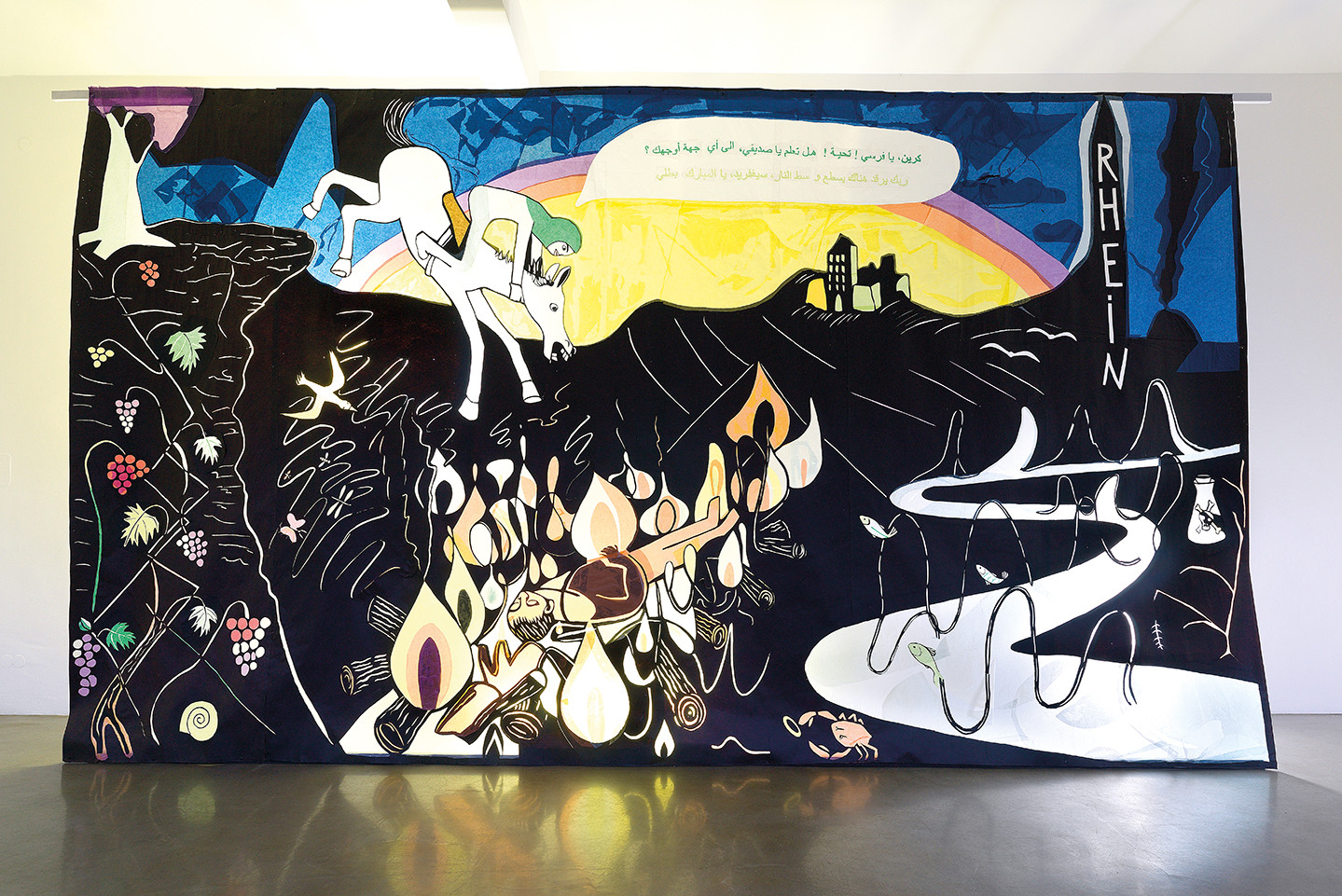

Indeed, for this exact reason, as well as others, few sculptural practices could be more appropriate to represent our fall, because in a way it’s all there. Dealing with everything from the hubris of human beings vis-à-vis the animal kingdom to our idolization of petroleum to idealized harmony between different species, Saeed’s work strikes me as the perfect three-dimensional and pictorial candidate to tell our tragic tale. And yet it is of course not all tragic. For there is much joy, love, and even compassion in what Saeed makes. This too is a crucial part of our story, which she does not neglect to tell. Saeed graduated from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2001, where she studied with Anthony Cragg, and has been actively making work for more than fifteen years in Berlin. While she has been exhibiting for over a decade, supported by her main gallery, Jacky Strenz in Frankfurt, with whom she has been affiliated since 2007, her work is just now starting to get visibility in a broader sense. In 2016 she participated in the 9th Berlin Biennial, and then in 2017 I invited her to do her first solo show in Latin America at Lulu in Mexico City. She also participated in the Köln Sculptur #9, curated by Chus Martínez, and at this moment is preparing a solo at Studio Voltaire in London and a two-person show at What Pipeline in Detroit, among other things. Interest in her work, from a variety of quarters, is on the rise. It wasn’t always this way. A proverbial slow burn, Saeed and her work have been anything but an overnight success. Why is this? I think it has as much to do with subject matter, as well as the philosophy and activism that drives it, as it does with the materials she uses. In many respects, she was, quite frankly, ahead of her time—a good decade ahead—and one of the main reasons this work has suddenly come into our purview is not because she is catching up with us, but because we are finally catching up with her.

Saeed makes sculptures, sculptural reliefs, drawings, works on paper, and video, and is known to use nontraditional materials, such as and especially Styrofoam. The work is directly linked to and thematically informed by her interest in animals and her commitment to animal activism. It deals with the exploitation of animals, their depiction, liberation, and potentially harmonious relationships with human beings, and the often self-seeking meanness of the latter. Normally I might be dubious of the harmonious coexistence and synthesis of such a specific political position and the formal qualities of a sculptural practice, but there is virtually no gap between Saeed’s thinking and her making. It all coheres into a fully integrated whole. Consider for instance her proclivity for Styrofoam. While some might perceive an ideological discrepancy therein, they would be mistaken. Saeed is drawn to this material in large part for its ugliness. Traditional sculptural materials such as bronze and marble are, as far as she is concerned, too beautiful, or too easy to render beautiful. For her, the uneasy complexity of Styrofoam reflects the complexity of the subject matter she is dealing with, while presenting a host of real sculptural challenges. I think it is also thanks to this material that she has been relatively eclipsed until recently and simultaneously embraced by a whole new generation of practitioners. For more seasoned professionals, it might have been hard to see the use of this highly unnatural material as sculpturally valid, while for younger professionals who naturally possess a more elastic notion of what is materially interesting, it is a given. Granted, Saeed is far from the first artist to work with Styrofoam; one might immediately think of Huma Bhabha, a decade her senior, whose work is much more archaeological. Saeed, for her part, uses the material in a way that almost always foregrounds it as such. Never dissimulated behind craft, the fact of its being Styrofoam is almost always visibly essential to whatever she depicts, insofar as its globular porosity functions as part and parcel of the texture of a given piece. Indeed, cognizant of its fickleness, Saeed even yields to and arrogates a minimum of autonomy to the material—allowing it, to a certain degree, to do what it wants to do.

All that said, its fickleness informs the apparent simplicity of her iconography, which includes everything from Egyptian statuary to Greco-Roman friezes and references to European modernism (for instance Max Ernst) and scientific and natural history museum displays. It’s as if the limits of Styrofoam coincided with the relative, seemingly naive rawness of her iconographic intentions. Initially it might seem that these intentions replicate the so-called primitivistic fetishism of continental European modernism, but if they do so, it is for a very specific reason. When not depicting acts of violence, oppression, or animal liberation, Saeed presents tableaux in which animals and human beings celebrate the recent liberation of animals from their cages with an idealized, nonhierarchical abandon that has if not an antediluvian aesthetic, then a markedly prelapsarian quality (see for instance The Liberation of Animals from Their Cages III [2008]). One thinks indirectly of everything from Sumerian reliefs to Egyptian sculpture to all manner of pre-Colombian imagery. Thus if she is drawn to the alleged innocence of this pictorial language, it is not due to a fetishization of innocence as such, but because of its representation of a time in which animals and human beings supposedly coexisted in a kind of halcyon harmony. And yet for all its apparent simplicity, the work is quite sophisticated from an anatomical and biological point of view. Saeed once told me how the German artist Jochen Lempert, who has a degree in biology, correctly identified prehistoric protozoa in one of her reliefs based exclusively on her depiction—which is to say nothing of the complexity of the work on the level of composition, color, and formal inventiveness.

Another important element that has helped bring this work into focus is a philosophical, even political paradigm shift that has been taking place over the past decade. This shift has been fueled as much by developments in continental European philosophy, such as object-oriented ontology, as by the emergence of the geological paradigm of the Anthropocene. These changes have necessarily been accompanied by a revaluation of the human relationship with the natural world, and more specifically with animals. To this end, Saeed is one of a dozen or so artists who are currently considering these issues—they include Pierre Huyghe and the already mentioned Lempert—but none, as far as I can tell, operate in an explicitly political, even activist fashion like Saeed. Her personal politics are inseparable from what she makes and how she makes it, and she has no qualms about communicating her position and advocating for the rights of animals. Saeed even includes in her solo presentations texts by animal rights activists and philosophers such as Melanie Bujok. In the case of Djamil at Lulu, a bilingual photocopy of a text by Bujok was located under a welded copper lobster, which the viewer could take away at will—the text, that is.

While it is hard to imagine appreciating Saeed’s practice if you’re not sympathetic to its political convictions, it is not, I believe, a prerequisite (but then again, who doesn’t like animals? Who among us, if pushed, wouldn’t be open to a more equitable relationship with the animal kingdom?). Interesting on a multitude of levels, Saeed’s work never takes its form or medium for granted, whether it be a wall drawing, a free-standing sculpture, a frieze, or the occasional video. She continually interrogates material and formal qualities, seeking out the best possible solution for her politics and her work.

Chris Sharp is a writer and independent curator based in Mexico City, where he co-runs the project space Lulu.