Lin May Saeed: Arrival of the Animals

Is this a time in which we can earnestly view artworks which center nonhuman experience? In this moment of social and political precarity, in which protests demanding resolute action against the systemic murder of Black Americans are ongoing amidst a dehumanizing global pandemic, can we engage with a practice that asks for a critical reappraisal of interspecies relationships? Lin May Saeed has been intimately concerned with animal-human interactions for the past 15 years, and her works illustrate scenes of animal liberation, cohabitation, and subjectivity. Employing distinctive iconography, and drawing on various media, Saeed creates works that cast animals—lions and panthers, bees and water buffalo, calves and a pangolin—as protagonists, graceful and tenacious in the face of violence and habitat devastation. Their potency lies not in the request that we look momentarily beyond human experience, but in a deeper, more urgent appeal to understand ourselves as part of a connected whole. Saeed’s is an empathetic practice, one which cautions against solipsism while demonstrating its dangers on varying registers.

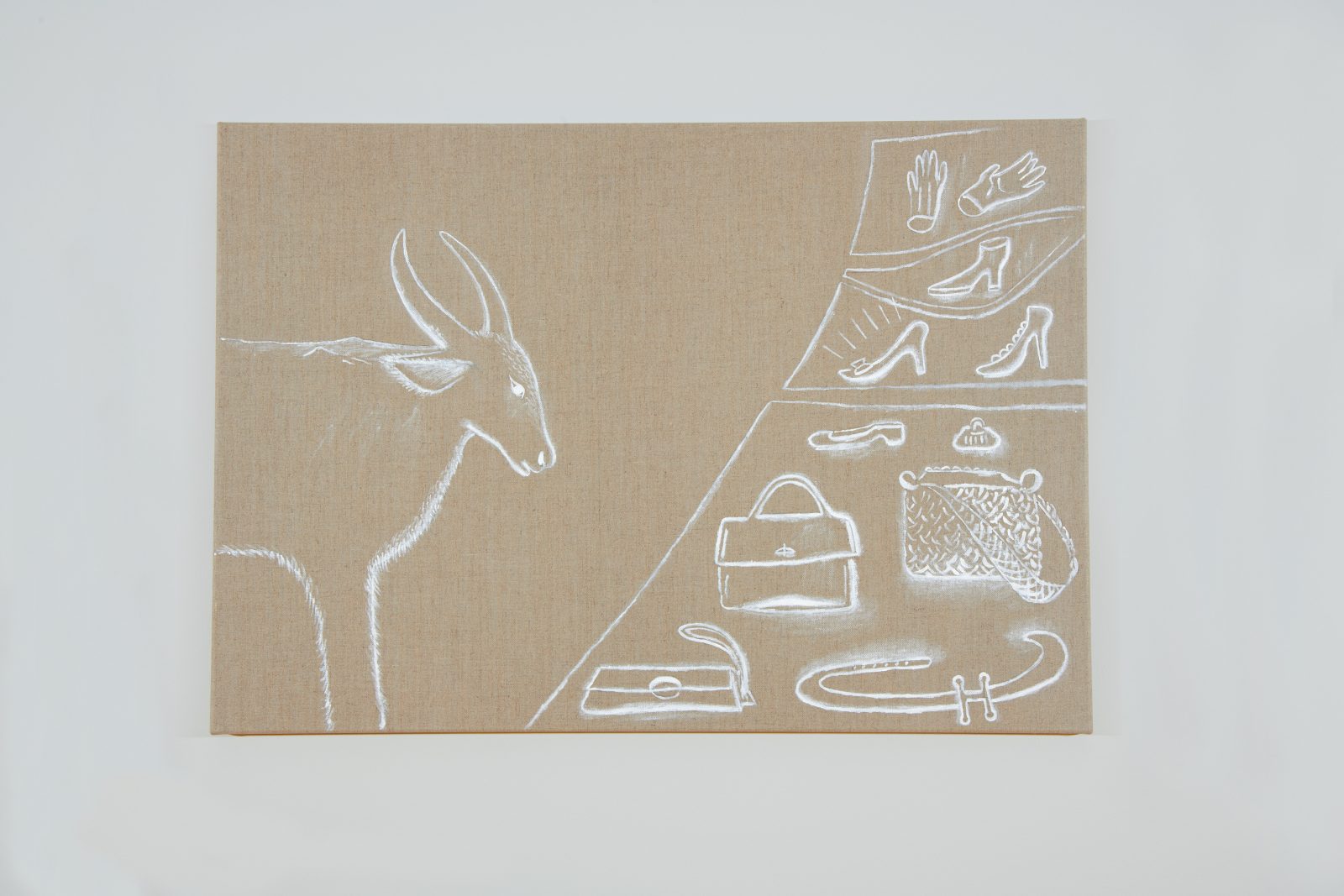

Arrival of the Animals, on view at the Clark’s Lunder Center in Williamstown, Massachusetts, is Saeed’s first solo museum show. The exhibition, curated by Robert Wiesenberger, takes its name from a short story by the Nobel-prize winning Austrian British author Elias Canetti. Like Canetti’s works of literature, Saeed’s practice is at once deeply psychological and disconcerting, and draws on imagery from history and mythology to illustrate encounters between animals and humans. The artist is perhaps best known for her reliefs and sculptural works crafted out of polystyrene foam (commonly referred to as Styrofoam), while welded steel “gates” and works on paper also populate the gallery’s walls. Each of the 21 pieces presented here retains a stark sense of narrative, in which animals are drawn and painted with an earnest vitality usually reserved for biblical prophets or mythological heroes.

In Panther Relief (2017), a large lunette of carved and painted Styrofoam and wood, the titular feline floats in a murky pool. Delicately etched reeds and water plants occupy the foreground, while a scene of industrial detritus recedes into the distance: crumbling façades and fallow fields, a rash of barbed wire and an abandoned cityscape. In spite of the destruction, Saeed’s message is prescient rather than cautionary. At home among the ruins of this post-human scene are deer, dogs, birds, and other ambiguous fauna which appear at ease alongside the relics of our self-absorbed projects of modernity. What we’ve forced out will return, Saeed seems to tell us, and will bring with it a vibrance we can’t anticipate.

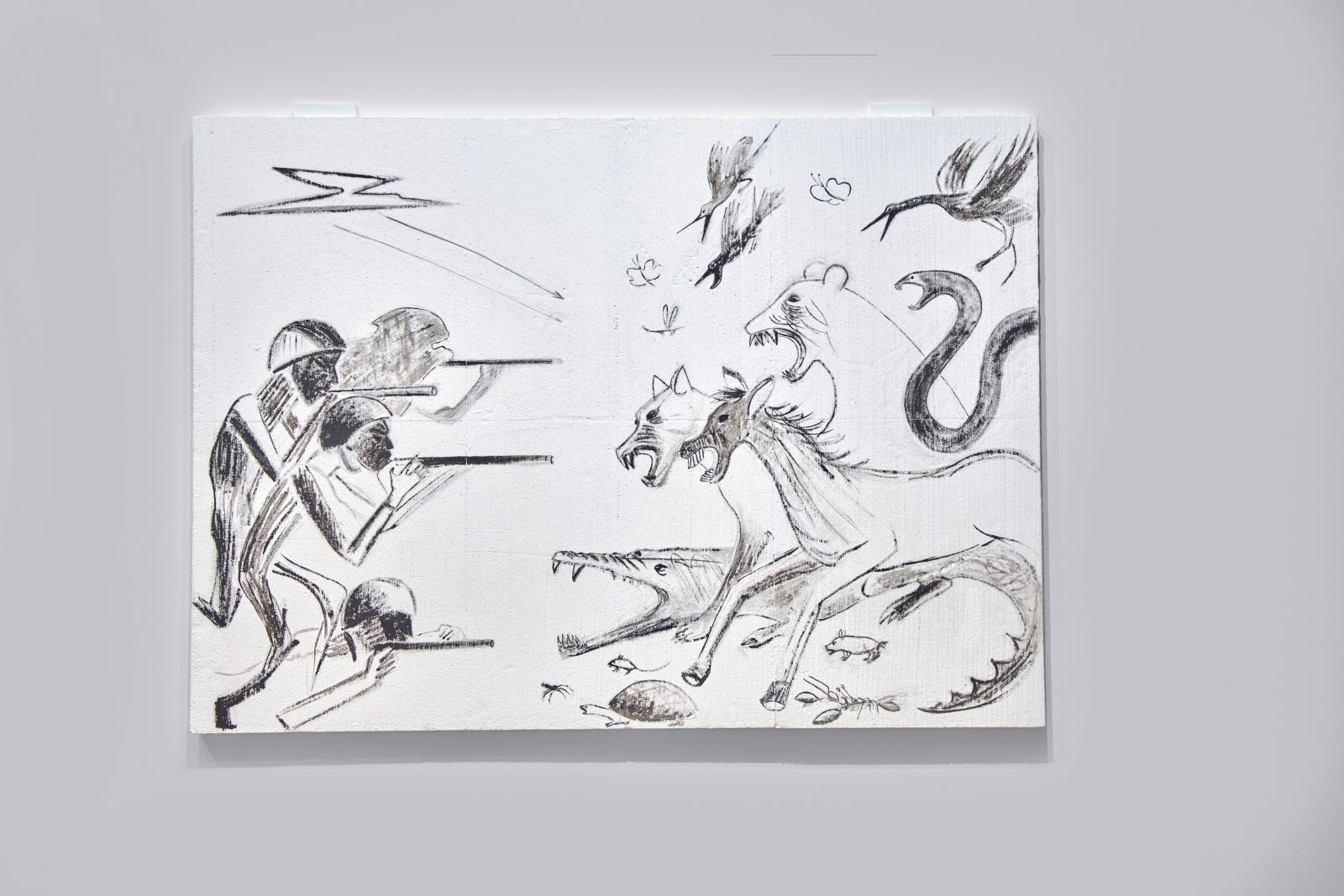

Saeed’s polystyrene works are occasionally compared to Huma Bhabha’s, a pertinent association given both artists’ interest in subjectivity. Yet where Bhabha’s figurative sculptures examine human experience, Saeed’s encourage a discernment about our relationships to our nonhuman counterparts. Her use of Styrofoam raises a freighted paradox: she is clearly concerned with the ways in which humans and animals coexist, and frequently (as in War [2006] and Aynoor [2020]) casts mankind as the antagonist, highlighting the estrangement between species and bluntly illustrating the human capacity for violence. Yet violence feels implicit in the choice of Styrofoam, which is commonly associated with waste and pollution, an artifact of the damage humans have inflicted on animal habitats. The material, crafted from petroleum, takes at least 500 years to decompose (in some conditions, it is estimated to last over a million years).

To be reminded of the violence of most human-animal relationships is sobering; to be confronted with the longevity of that violence is almost incomprehensible. In her delicately crafted works Saeed shows us that temporality in the climate-controlled gallery space cannot, in fact, be divorced from the passage of time in the landfill. The harm we inflict on animal life, whether knowingly or inadvertently, is not presented as an abstraction. Rather, it is illustrated here by means both literal and metaphorical. Walking through the Lunder Center I was reminded of Eva Hesse’s latex works, which exemplify the transience of some industrial materials. But where Hesse’s geometric forms have browned and withered, Saeed’s Styrofoam will likely retain their shape and color for millennia. They will endure, like the fauna in her reliefs, in spite of humanity, in spite of our projects of ecological dominance and our gross neglect of the world around us.

Saeed’s steel gates provide a counterpoint to her Styrofoam works. They are solid, sturdy, and (perhaps most curiously) functional objects, complete with hinges and latches, which appear decommissioned when hung on the gallery wall. While much of Saeed’s work has a graphic quality, the three gates on view (Toreador Gate [2019], St. Jerome and the Lion [2016], and The Liberation of Animals from Their Cages XXIII/Djamil Gate [2020]) are completely, almost bluntly, pictorial. They distill the artist’s project into dark lines and curves, each featuring a scene of emancipation: a bull runs over its human captor, a masked figure clips a rope tethering a camel to a post; the robed St. Jerome plucks a thorn out of the lion’s paw. If Saeed’s practice emanates from the idea of liberation, these three objects in particular suggest the way forward. The humans featured here are either integral to or overwhelmed by animal liberation. It is a question asked of the viewer, one which both elicits and instructs our capacity for empathy.