- Dates2 May 2014 - 28 June 2014

- Artists

by Gertrud Sandqvist

“Doesn’t the analogy between language and games throw light here? We can easily imagine people amusing themselves in a field by playing with a ball like this: starting various existing games, but playing several without finishing them, and in between throwing the ball aimlessly into the air, chasing one another with the ball, throwing it at one another for a joke, and so on. And now someone says: The whole time they are playing a ball-game and therefore are following definite rules at every throw.

And is there not also the case where we play, and make up the rules as we go along? And even where we alter them – as we go along.

(Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations , paragraph 83)

In Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein cleans up everyday language for us, so that we will also be able to use it when we do philosophy. He lays out all the possibilities of language, and combines propositions together, so that we understand his metaphor for language – a toolbox, in which not all the tools are suited to the same task.

Heimo Zobernig does something similar within visual art. He lays out all the possibilities – painting, sculpture, film, the pedestal, typography, the title, the catalogue, partition walls, lighting, stage construction, floors, ceilings, chairs, tables, the artist function and the curator function, the seminar – and sees how they can be combined or refined and, hence, perform a new, artistic, meaning-bearing function. Occasionally, a new function, a new “tool”, is introduced, but not particularly often, and not without mature consideration. And then he tests out and varies the possibilities of his arsenal with each new exhibition or project that he is invited into, or which he occasionally also initiates himself. The language game, to use Wittgenstein’s term, that he participates in and which he himself shapes, has proved to be extraordinarily flexible, and has made possible around thirty exhibitions and projects every year for thirty years! Whether the artworld’s interest in Zobernig’s work centres on its institutional critique or, on the contrary, on its solid late modernism seems of little relevance. What is important is that Zobernig has figured out the complex machinery that constitutes the way that an art exhibition constructs and bears meaning.

It is symptomatic that more analyses and texts have been produced about Zobernig’s art than about that of almost anyone else of his generation. And as evenly as his exhibitions and projects are spread throughout the decades, it is equally interesting for critics to write about his work for decade after decade.

Artists of Zobernig’s generation are called postmodernists, either because they shift the focus to the viewer/reader/listener and are interested in the actual meaning creation in art, or because they see that it is enough for the artist to create a structure. It is the viewer, or life, that fills it with meaning. It was this phenomenon that led the minimalists to try to avoid anything that could be associated with the human hand, and hence with personal expression. The postmodernists accept the fait accompli , rather than avoiding it. And Zobernig, at least, feels no anxiety about the artistic subject. It seems as though he sees it as one function among other functions. Here his training as a stage designer may play a certain role, along with all the experimental-theatre works of his youth.

A text that was to be one of the most important for the early postmodernists – even if Zobernig himself does not refer to it explicitly – is Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility from 1936. Here Benjamin proposes that the whole of our seeing and our relationship with the artwork has been transformed, not only through the technically possibility of reproducing the artwork, but also above all through the new media: photography and film. Instead of cult value, what now emerges is exhibition value. He writes: “With the emancipation of specific artistic practices from the service of ritual, the opportunities for exhibiting their products increase.”

Benjamin is extraordinarily radical in his analysis: he maintains that when the magical value, or what he calls the cult value, of art has disappeared, totally new possibilities open up for the artwork. As soon as the work of art is recognized by its exhibition value, rather than its cult value, it can even be the case that what he calls “the artistic function” becomes incidental. Other functions emerge in its place. One of these is play or the game, which, according to Benjamin, becomes an increasingly crucial aspect of the artwork the further removed human beings get from their urge to master nature through magic.

When Benjamin turns to film and proposes that film actors do a “test performance” in front of the camera, rather than actually playing a role that they can identify with, like theatre actors do, this becomes really interesting in this context. Benjamin specifically claimed that, in their quest for authentic characters who would simply be themselves in their films, Russian filmmakers see the actors themselves as props. They need a certain type, a certain external appearance, rather than an actor.

And then Benjamin comes to his famous simile, in which he compares painting and film photography to the relationship between the healer and the surgeon. Just as the healer heals with magic, with laying on of hands, and distance, the painter needs a certain distance from reality. The cinematographer, in contrast, goes deep into the substance of reality, and uncovers things that the human eye is unable to perceive.

Three things are interesting here in relation to Zobernig’s practice. They apply to his relationship with painting, to the way he uncovers the exhibition space, and to the way he uses his own subject.

Adopting Benjamin’s metaphor, we can say that Zobernig is both surgeon and healer. In an early text, the foreword to his first major museum show in Austria (Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, and Salzburger kunstverein, 1993), he describes the artist’s new possibilities within a system that no longer has any fixed boundaries, but which instead emerges as a complex network. But he objects to the way that this would also imply an end to aesthetics. For, in such a case, he writes, this would also mean an end to art.

Here, Zobernig’s stance differs from that of conceptual art, and also from the stance of institutional critique: that the artist and/or institution decide what is art. His emphasis on the significance of aesthetics is reminiscent of Immanuel Kant’s disinterested object, worthy of being contemplated in its particularity, its unique beauty, and specifically through its uselessness for any purpose other than contemplation, the viewer practices self-forgetfulness, and thereby objectivity.

The disinterested object corresponds fairly well to Benjamin’s “healer”. The effect happens at a distance.

All the possibilities that Zobernig sees in being able to operate in an extended spatiality and contextual field correspond to the surgeon’s incision, or to what Benjamin calls exhibition value.

We could say that what makes us recognize an artistic incision into a space, an architecture, a situation like a work by Zobernig, specifically depends on an altogether special aesthetic, a way of relating to proportions and functions.

His painting becomes a special case of this universal aesthetic attitude.

Aesthetics, or an even more highly charged word, taste, is not a private matter, utilizable solely for home furnishing. It is a way of apprehending and ordering the world. Marcel Duchamp understands aesthetics as something that is as personal and fundamental as handwriting – as something partly unconscious or, in any case, difficult to change. The special refractive lens of aesthetics means that people discriminate – that they prefer one specific constellation over another. Zobernig tries to counteract the effects of an overly narrow discrimination, for instance, through his systematic, encyclopaedic collections and surveys of certain areas of artistic interest. One example among many is seen when he compiles an impressive bibliography of everything that has been written about colour ( Farbenlehre , 1995), or when he adopts the printing colours (cyan, magenta, yellow) as his working material. But he can also – in an early exhibition (Galerie Holzer Villach 1991) – copy all the diagrams about how human beings experience colour from a scientific book about the effects of colour on people, as though to show how absurd is the idea that there is an objective colour experience.

Almost all young artists initially express themselves visually by starting to paint. This was also the case with the very young Zobernig. Some carry on, and subsequently choose painting as their primary means of expression, even if they try out other possibilities. Or then the urge to paint fades as other means of expression take over. This does not happen in Zobernig’s art. He continues to paint in parallel with incorporating a series of other possibilities into his artistic repertoire. He seems to appreciate being able to use the healer’s distance as well, at the same time as he performs his various incisions.

Exhibition value beats cult value on every level, Benjamin maintains. He was primarily referring to artists such as El Lizzitsky, Rodchenko and Tatlin. But there is a point at which exhibition value ceases, and that point is the human face. Cult value takes over, or – Benjamin is not entirely clear here – does the human face stand for authenticity?

Zobernig frequently appears in his own videos. I am particularly interested in three of them in this context. Video no. 6 , 1991, is a 30-minute video in which the artist looks us straight in the face. Video no. 12 , 1996, shows the overlaid image of the naked artist moving around in an architectural promenade through Chicago. Video no. 18 , 2000, shows the naked artist battling with large sheets of cloth in chroma-key colours, the ones used to allow the background in video recordings to be altered. The naked face, the naked body, the emblem of honesty, is here also the artist’s own. This is the artist’s person as one function among the other expression functions.

The artist’s own person, his own statement about his art etc., is usually ascribed an almost overwhelming authority. People very rarely go against the artist’s own words. But Zobernig uses his person – or persona? – without such weightiness. Simone Weil writes in a well-known essay about the difference between person and personality. I will travesty her and propose that we are seeing Zobernig’s naked artist person, not his impressive artist’s personality.

There is a series of such subtle apparent contradictions in Zobernig’s art. The foremost and most significant is that, when he incorporates into the gallery or exhibition space elements that are traditionally seen as having a supporting function, but are not the work itself, he does not call into question the concept of art, but extends it. Thus, the bar counter becomes art, like the pedestal, the shipping crate, the partition walls, the floor, the podium, the catalogue, the poster, the conversation, the discourse. If all these visually neutral areas are part of a meaningful discourse, it also becomes very difficult to distinguish the discourse from the work – and it is on this distinction that modernism’s art criticism depends. In The Creative Act (1957) Duchamp is the first to analyse the phenomenon, when he claims that an artwork is constituted by two poles – on the one side the artist, on the other side the viewer, who later becomes posterity. But, if the viewer is the one who gives the work meaning (which, as Duchamp writes, is “‘refined’ as pure sugar from molasses”), how can one then acquire the distance required for analysis? It gets even more complicated when the artist, as Zobernig does, maintains that he is more of a historian or a scientist than an artist. There is then a short-circuit in the traditional system, which assumes, for example, that art and science are each other’s polar opposite.

Instead, Zobernig seems to be proposing that art is one specialized way of analysing and acquiring new knowledge about how our visual and intellectual reality is constituted. In order to be able to be apprehended as art, this knowledge must be achieved through aesthetics. Without aesthetics art ceases to be art, and becomes something else. We then lose the very special tool, the lens that we call art. The contribution that Wittgenstein made to philosophy Zobernig makes to art. He shows all the words in between, the passages and highways of visuality, and refines them, making makes them useable for art.

Excerpt from Heimo Zobernig, 2013

by Arthur Fink, Terpentin*

The fourth exhibition of the Austrian artist Heimo Zobernig (*1958 in Mauthen, Carinthia) at Nicolas Krupp Contemporary Art presents pieces from a cohesive body of works:

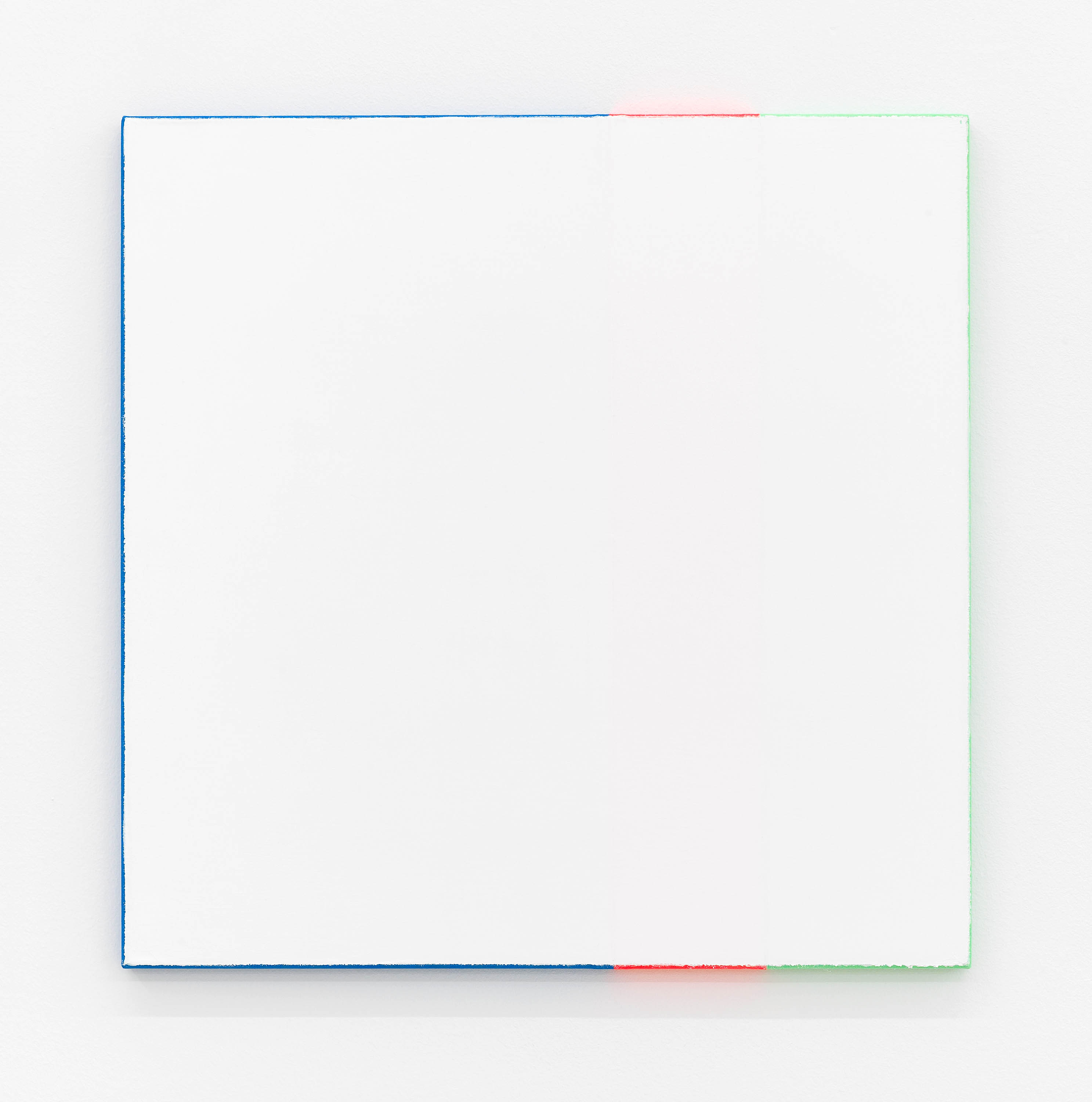

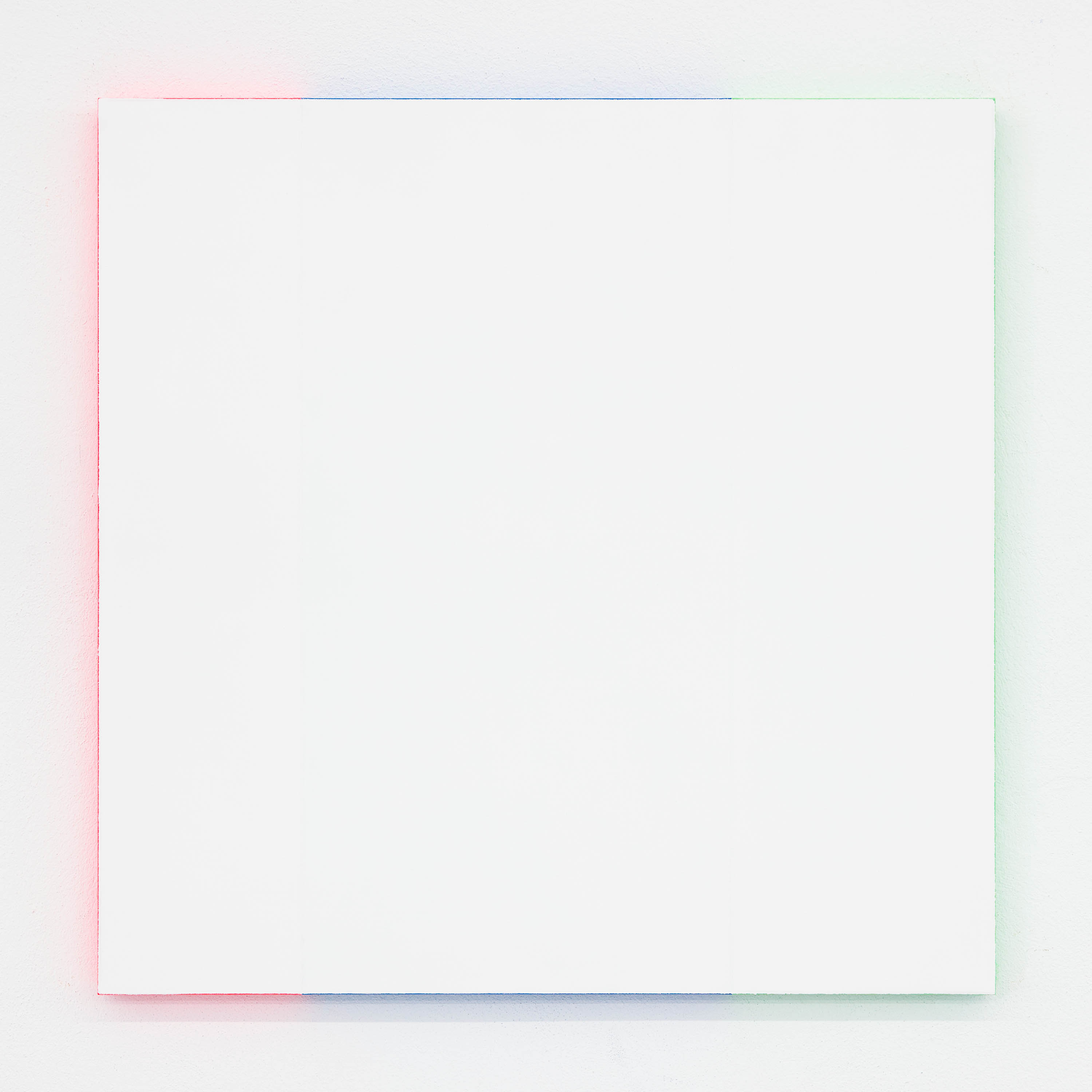

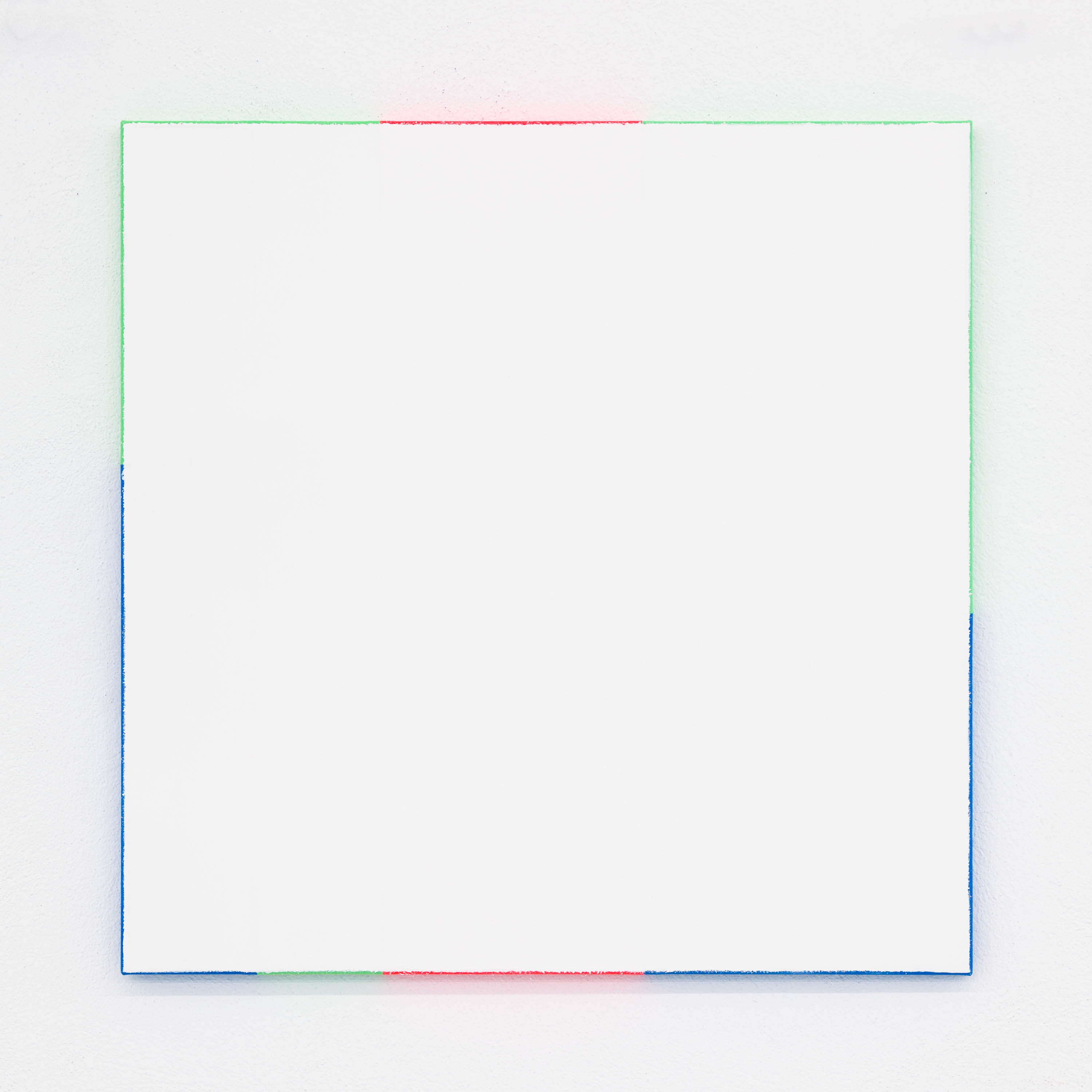

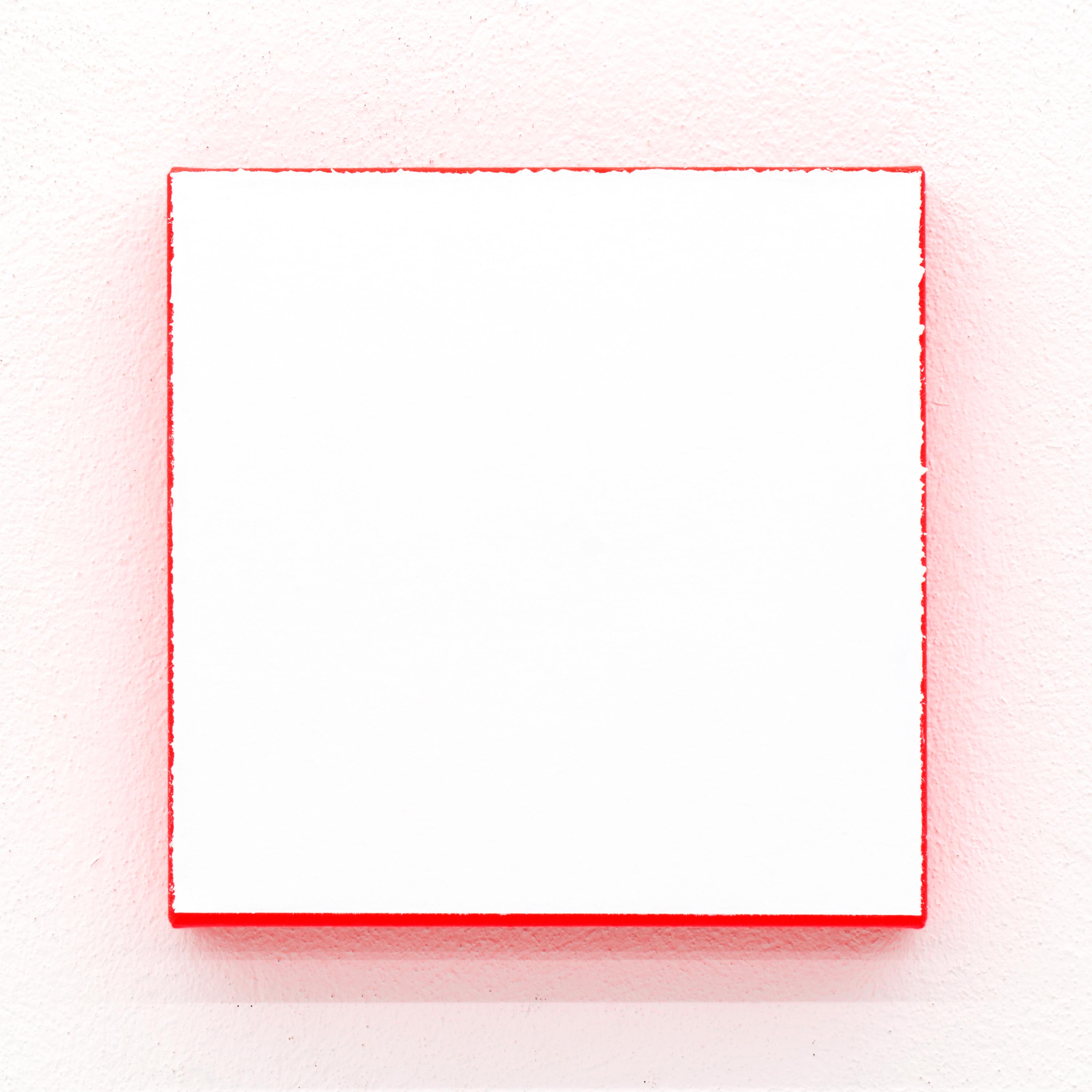

Upon entering the gallery spaces, one first sees everything in white—nine monochrome white tableaux are hanging on the walls—until one notices curious red, green and blue tinges coming from the sides of the individual “panel paintings.” When taking a closer look at the pictures, the reason for this emanation becomes clear: The stretcher frames are spanned with colored polyester fabrics, some with several sewn strips in the three mentioned colors, others in just one color. The colored canvases are overpainted with white—except for the side edges whose bright colors are reflected onto the gallery walls by the neon light.

The fabrics employed here as the painting ground are quite familiar from other works by Zobernig—fabrics used in TV and movie productions for so-called chroma keying, a technique with which figures are filmed against a monochrome background (in video blue, video red or green screen). This allows replacing the backdrop of the figure with an arbitrary one. The fabrics used as material carriers in these images are meant to disappear, allowing other spatial contexts of depiction to appear. They are backgrounds conceived for other backgrounds.

The white color constituting the painting as a painting seems to have been applied using a roller. The originally different colored canvases are painted like the background of the artworks in the gallery itself—white, like the walls of the white cube.

The chroma keying fabrics are carriers for something else, as is also true of empty canvases or white gallery walls. The white cell facilitates viewing art objects in a neutral context as isolated, independent forms. In this respect, they function similar to the blue, red or green box in the filmic method of chroma keying.

The tableaux in the exhibition are conceived in such a way that the reception process is predetermined. The viewer registers the visually unambiguous information as if he or she were in a show displaying abstract white pictures. Since, on the level of the technical make, the works reveal something seeking to be decoded, the viewer steps closer. Upon approaching, the material raises questions triggering an interpretation process that turns the viewer into an actor in a choreography formulated by the artist.

The peculiar quality of the paintings is reinforced, if not evoked, by the neon light and the color of the gallery walls. The visual attraction inherent to the paintings is precarious, since it is made visible only by the neon tubes in the white cube. If these panel paintings would be viewed in private spaces, where the lighting is rarely optimized accordingly, the side edges of the pictures would no longer reflect evenly or at all. Outside of the gallery, the painting could very well lose its nimbus.

In addition to these interpretations derived from the material properties of the works, other approaches suggest themselves. The paintings could be read as a contribution to various debates in the discourse of art since modernism, for example, as an examination of the relationship between painting and video, or as a continuation of the modern discourse on the panel painting, since, after all, the pictures are all “white squares.” The works could also be situated in a discourse on Minimalism or read as a formal deliberation on the relationship between material carrier (canvas) and picture, because it is the material carrier that makes the picture a picture which can be distinguished from the wall. One can also interpret them as a problematization of the culturally highly valorized panel painting, if one grasps the pictures as pure functional carriers within the gallery space—as objects whose purpose it is to be turned into an aesthetic experience through the beholder.

All of these aesthetic debates resonate, but they don’t get us very far; Heimo Zobernig merely cites them and thus holds a mirror up to the viewer. He demonstrates how the gallery-goer approaches the works by means of traditional cultural interpretation keys. The pieces are overloaded with discourses, and that’s where their potential lies. They are recalcitrant provocateurs exposing the mechanisms of producing meaning.

Hence, one turns into the witness of one’s own mechanisms of attribution, becoming aware of one’s projections when walking through the gallery—projections evoked by the history of theoretical and artistic engagements with the format of the tableau.

*read original Terpentin article, 29 September 2014

Contemporary Art Daily, 2 July 2014

Heimo Zobernig

The work of Heimo Zobernig (b. 1958, Mauthen, Austria) spans an array of media, from architectural intervention and installation, through performance, film and video, to sculpture and painting. His practice across all these forms is connected by an interrogation of the formal language of modernism, at its most familiar in the tropes of the monochrome and the grid, yet also concerned with Constructivism, colour theory and geometric abstraction.