- Dates4 July 2008 - 30 August 2008

- Artists

by Jean Marc Huitorel

The principle of duplication, which is the most obvious characteristic of Bernard Piffaretti’s art, has had countless repercussions, the most disconcerting of which and one that is rarely mentioned today, is that it has even been taken up by the critics of his work. So many things are repeated from one text to another, so many never-ending new beginnings in order to say something about a work that distinguishes itself through the very idea of starting over. It’s enough to make one dizzy. Glossy criticisms and exegeses for a text that is so clear yet so murky at the same time. Reiterating the facts each time is inevitable. Next, choosing from the inexhaustible stock of banalities a few that aren’t too threadbare and fashioning them into pretty sentences, between the arrogant starchiness and flippant joking (that remain, what-ever one may say or do, the undeniable and very ambiguous bipolarity of this universe).

There is a history of French painting, and within this history that is itself a part of the more general history of painting and of art, there are certain points that light up and that blink insistently. Take, for example, the Ecole de Fountainebleau: one would almost say that it involves only one artist, so completely has the term replaced the usual patronyms of the artists. Then, look at 17th century painting, prior to the great decorative projects. For yet another example, after so many guilty omissions, take Manet and then Cezanne who ushered in the international modernity of a 20th century that would indeed be both modern and international. In this century, the French artists would go and come between the luminous openings and the unyielding confines of artistic identity. After the trauma of the 1964 Venice Biennale that witnessed the revenge of American art, thus rectifying the no less traumatic affront caused by the 1913 Armory Show, French painters operated discretely within their own country.

Isolated but not lacking in well-established mentors, (Simon Hantai, for example, considerably influenced the development of Michel Parmentier’s work), they lived in a very combative but also very productive way during a time of constant flux between the Americanism arising from the New York School and then from Pop Art and a nascent globalization that was certainly dominated by the United States, but that was nonetheless nourished by artists of very diverse geographical origins. This transition from the modern to the postmodern, which in France occurred between Supports-Surfaces and Figuration Libre, was affirmed in West Germany through the work of Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, and through early Jonathan Lasker, Helmut Federle, Peter Halley, Christian Bonnefoi or Pierre Dunoyer.

During this same period that saw the rise of Figuration Libre, Trans- avant-garde, Nouveaux Fauves and the different strains of Expressionism, a few young people were finishing their studies at Beaux-Arts Schools (or elsewhere). They didn’t necessarily know each other (in no way whatsoever did they constitute a group or a movement) and their names are for example, Herbert Brandl, Christophe Cuzin, Helmut Dorner, Albert Oelhen, Jean-Francois Maurige, Adrian Schiess or Bernard Piffaretti. Each in his own way, they were painters caught in an extremely complicated (not to say unlivable) time period. They were undoubtedly familiar with the retrospective inventory of Richter and perhaps even with the facetiousness of Bernard Frize who wanted to liquidate modernism, but whose works proved too ironic to offer any truly new perspectives. As for Piffaretti, he turned his gaze towards artists such as John Armleder whose artistic activism he found more relevant. So on the one hand, there was the legacy of Supports/Surfaces and BMPT (Buren, Mosset, Parmentier, Toroni), as well as of minimalist painting, and on the other hand, the so-called alternative of the cultivated reference or of “youthful” spontaneity. Nothing particularly exciting there, worse, a deceptive situation where trendiness was masking an artistic desert.

Instead, what was needed was to reopen the debate that Viallat, Dolla, Devade and Pincemin had left unresolved 10 years earlier, even more so because Richter, Polke then Heilmann, Pincemin or Federle had already reconfirmed the return to painting, and had proven that it still had the potential for adventure and artistic investigation. This was particularly true since the return in full force of the (photographic or pictural) image made the necessity of choosing between abstraction and figuration useless and laughable. What was urgent was to create a synthesis of the intellectual attainments of deconstructionism and a certain faith in painting that would be a lucid belief, one whose irony would remain sufficiently respectful that it would not become counter-productive; and this synthesis needed to find its place within the general movement of art, albeit in a falsely marginal position, if necessary. In other words, being able to make real paintings that testified uncompromisingly to an age that was confused, eclectic and adaptable. Voilà, the main features of the context of Bernard Piffaretti’s beginnings, a young artist whose apparently abstract works did not satisfy him and who was seeking a way out, that is to say, his own path.

After finishing his studies at the Beaux-Arts de Saint-Étienne and up until he progressively perfected his method which is a gradual process of working out the painting at the same time as it is a true manifesto, Bernard Piffaretti was seeking the most suitable means for his artistic objectives. In the early 1980’s, within the context described above, he was trying to produce a kind of painting that presented an ensemble of original objects, the fruits of a unique adventure and the stamp of the indispensible historical inscription. In fact, no serious work can exist without addressing this question, not only in terms of the artistic situation, but even more in terms of painting itself.

Very early on, Piffaretti was wary of immediate and spontaneous express-ion, of the expressionist stroke just as he was of anything that could evoke the idea, the affect, in one word, the style (since, if there is a method, almost a “Piffaretti system,” there is not, strictly speaking, a “Piffaretti style”). And if his first paintings reveal numerous lines that roughly suggest open shapes or which lay the groundwork for more chromatic displays, he returned pretty quickly to using collages and screens which already imply distancing and separation. That is where one must look for the origin of the “duplication as method,” but for right now, we can talk about a kind of painting that is more self-referential than lyrical, more centered around the question of the canvas, around the future of painting, than around the rumblings of the real world or the inconstancies of the heart. Bernard Piffaretti’s objectives have more than one thing in common with François Morellet’s. Other than sharing a crypto-dadaist attitude (which, against the grain of the fixed categories of the “official” version of modern art history, stands out as a constant in 20th century art), both artists intend at heart to empty the painting of any trace of premeditated emotion, to keep subjectivity at bay. To do this, they each adopt different processes, methods and procedures which have their own specific results; these are also what reveal everything that differentiates these two artists who, in the end, are actually quite far apart from each other in terms of generation and positioning. By not endowing their canvasses with emotions or ideologies, Piffaretti and Morellet transform them into a kind of demilitarized zone, (a proposition certainly), but one which in no way interferes with the viewer’s freedom, and so is a very anti-authoritarian act. Thus, as has already been expressed so well, it is the viewer who makes the painting. The ball is in his court, and within this court, anything is possible, including delight, intellectual questioning, and why not? – emotion. In any case, these two artists may not share the same kind of detachment. In Morellet’s work, for example, the uncertainty takes the place of the method, not so for Piffaretti. One is sarcastic, the other is not. This one seems to be saying “So, what do you make of this?,” the other concentrates on constructing a methodology of the regard. Morellet, the facetious one, gives a firm kick in the rear end to the more uptight kind of geometric abstraction, whereas Piffaretti gives himself up to the joys of a drily witty literalness where discipline and derision are indissociable.

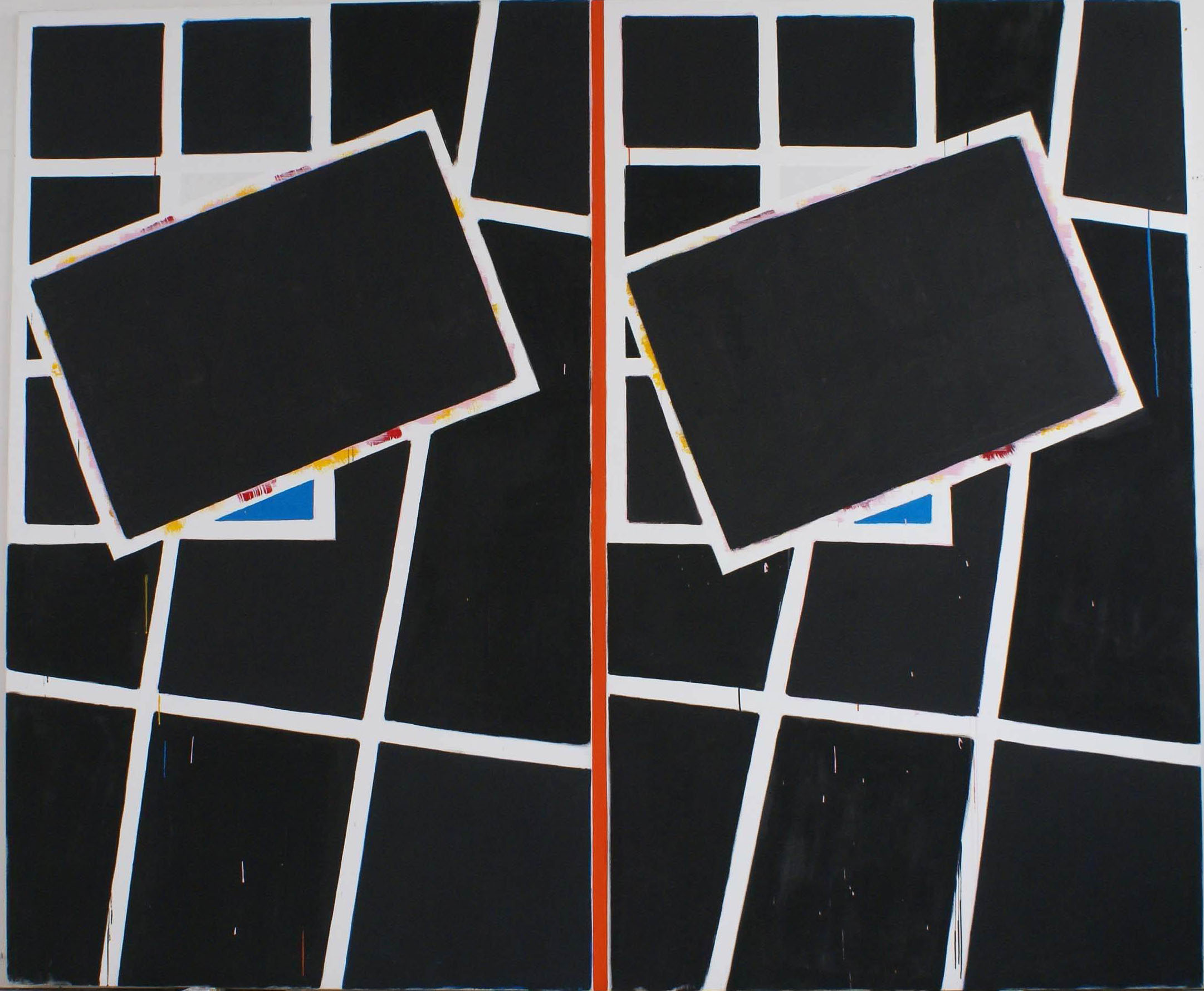

To describe the method that Bernard Piffaretti perfected towards the end of 1985 (although some 1984 paintings already contain the essence of the vocabulary), let’s use a sports metaphor. Let’s say the canvas is an athletic court: it could be for handball, basketball, or tennis or even be a ping-pong table since all these surfaces are divided centrally by one median line. Sometimes the action takes place on the right side, sometimes on the left. The match can thus begin. Of course its outcome is unknown. No one play resembles the preceeding one. It even happens, although rarely, that the game is interrupted by the referee. On the canvas, Bernard Piffaretti draws a vertical line that divides it in half. The line is suficiently thick to be very visible; its color varies from one painting to another; its thickness, on the other hand, remains ostensibly the same, so that a small painting by Piffaretti is never the reduced version of a large one. Next, the artist paints one of the halves, sometimes the left one, sometimes the right, (most frequently the left). When he judges this surface to be sufficiently painted (and the criteria vary, from one simple spot of paint to numerous adjustments of often complex pictural situations), he proceeds to duplicate it on the remaining half. Duplication does not mean a strict copy or an exact clone. Piffaretti is not trying to be his own copyist. No, it’s enough for the viewer to realize that the right half sufficiently resembles the left half (or inversely) for there to be no doubt about the deliberateness of the duplication. But a method, as we well know, necessarily has a purpose: to learn English, typing, or the guitar. And the finality of the “duplication as method” has little to do with that of Hantai’s “folding as method.” In fact, as we have said, Piffaretti’s method is not very strict (much less, for example, than those used by Morellet). One can even detect a few cracks in it, as if show that the artist is not obsessed with the exactitude of the duplication. In one small 1998 canvas, the separating vertical line is red, as are the two parts where seven small soft white squares appear, as if flying through the air. The red of the line is the same as of the surfaces. Thus, in order that one can discern the line, Piffaretti separated it from the lateral parts by two fine white lines, one on each side, which created symmetry (of chiasme, so to speak) but not of duplication. The same is true for the 1993 pink painting which belongs to the Foundation Cartier, as well as for a few others. One can see there a desire to destablize the strict ordering of the painting, as if one had sacrificed the ostentation of the central line to the unity of the whole. And then there are all those paintings in which both parts contain vertical lines that compete with the central dividing line, that indeed camouflage it within a forest of similar ones. It is like in an Alexandrine line, when the caesura to the hemistich does not exclude the possibility of making other smaller breaks that divide it on either side of the axis. The viewer’s attention is flustered for a moment, but then, once the disturbance has passed, he sees with relief that yes, in fact, everything is there, it was only a false alarm.

The principle of duplication includes some variations that are less the gages of virtuosity than tentatives of complexification of the questions it generates. For example, there are the small canvasses that include only a black vertical line; there is no trace of paint on either side (except, as in 1995, when a stroke of white appears, or most frequently, different hues of collage papers, that make many different kinds of white), however, obviously, there remains always the duplication of this “nothing,” the most perfect duplication possible. Few, these are made from strips of canvas leftover from that year’s paintings. The thickness of the central marking varies from one painting to another. These works almost always follow a period of intense production, as if the artist needed to take a break. The artist describes them as “sub-products”, or even as “by- products for personal use.” Their varied shapes – square, rectangular, round, oval – correspond to the typology of paintings available on the market. In this way, they seem like a vaguely ironic window, an escape towards the real world, its objects and their movements. In a certain way, their function is similar to that of drawings.

In other respects, something should be said about the Inachevés [Unfinished works] which the artist has been producing since the mid-1990’s. These consist of painting one side of the canvas and not duplicating it (the vertical line, however, is still there). This decision is not made in advance. It is made during the painting process when too many pictural acts, too much complexity render duplication difficult. That is when the artist decides to stop there, to leave the second surface blank. Paradoxically, these paintings do not give the impression of saturation or of complexity; on the contrary, they appear to contain a kind of obvious simplicity. The artist has subjected the painted half to an additional treatment, burying the various layers of the process either by “diluting” it in white, or by recovering certain zones. Sometimes the right side is missing, sometimes the left. In this case, it is not the painting that is unfinished (since it is exhibited and eventually sold as is), but rather it is the process. And perhaps more … The painting is like one of those hit songs where the singer need only strike up the first few notes in order for the audience to start singing along. Here, it is the viewer who finishes the painting. This collusion between the painter and his viewers is, as we know, an old story, that Michael Baxandall (1) has already masterfully discussed. But this blankness also means that the origin is in the moment, that everything happens within the act of duplicating (or within the decision not to duplicate). The origin is not the actual making of the first part of the painting, but rather its opposite whose visible mark remains the vertical line.

And finally, there is one last instance of duplication in Piffaretti’s work: the drawing after the painting. One can easily see the uselessness, indeed the inanity, of preparatory drawings or of any other kind of rough sketch in the sense that the painting encompasses the totality of the painting process. The drawing that comes afterwards, and that is always done on 21 x 29.7 cm paper format, is both an archival tool, in that way resembling photography, and a way of reproducing the visuals divorced from their context and from the specific intentions of a catalogue. It is also and above all a last ironic wink at self-appropriation (copying the masters), an ultimate way of duplicating, in a minor way, but this time, duplicating the entireity of the painting. The artist speaks of it as if it were a moment of idleness: “It’s like winding up a clock, rewinding a piece of time, to go a little farther while… running in place.”

The artist himself has discussed this duplication. During a symposium (2) he clarified a certain number of indispensible points in order to dispel any misconceptions. By the way, he is not indifferent to the fact that these remarks were included in a volume in which Sturtevant discusses the copy (“Exact and detailed copies lose all their power and all their energy through the rigidity of this technique, they become static and dead. The powerful creativity of the process is eliminated.”). I would like to refer the reader to this text by Piffaretti as well as to other writings (3) by the artist, but not without first quoting these few words: “Duplication is not a deconstruction because it reveals all of painting in one fell swoop.

It is a kind of apparition, a ‘conscious hallucination’ to quote no one. The more I show the primacy of the formal aspect, the more I escape formalism.” Later, he evokes the preeminence of the “second time.” It is a question of temperament as much as an esthetic position. Faced with the spontaneists who live only in the magic of the “first time,” at all times, there are those who can only take the step to act within the context (and the promise) of the second time, which is one of deliberate awareness and verification. However, there is no cynicism there, and even less melancoly; it has nothing in common with yet another crisis of painting or with the so-called and stupid impossibility of painting. No formalism either obviously since the method in no way resolves the questions of painting, it is simply a disciplined way to set apart the development and then the reception of the act of painting. It is not even a trademark (Villat, Toroni, Buren or Parmentier). It is the possibility of re-enacting the very history of painting in each canvas. It is a process that one re-enacts, a reconstitution (of a crime or of a primal scene). It is a narrative. It is endowing the space of painting with time. It is not to take the place of time, but almost; it is something like a method of deacceleration. And, because this temporality is entirely contained within the strict circumscription of the canvas, it loses its relevance there where, in the majority of artists’ works, one expects it, that is, in the succession of works, in the biographical unfolding of the entire body of the artist’s work. Piffaretti willingly says that he does not paint recent paintings. At one time, I thought that he was wrong, that through careful study, one could detect something like an evolution of the work, or at the very least, of periods. I thought that there was a time, for example, when he concentrated more systematically on producing a kind of painting that was denuded of seduction, on beating back any effect, at the limit of the (backswing), almost insufficient. It was an optical illusion. One needs only to browse through the many catalogues published since 1986 which show a very significant part of the work in order to verify the utter absence of chronological movement. This does not mean that all the paintings look alike. Quite to the contrary, this body of work is characterized by an extreme variety, a systematic variety. Another kind of vertical separation runs from one painting to another, an emptiness that slices through the visual and mental space, but the resulting repartition is the exact opposite of that of the paintings. Each new painting runs counter to the preceeding one, thus giving chronologogical development a jolt, countering the usual logic of what, in art history, one rightly calls “periods.” And this is what accounts for Piffaretti’s explanation of his work as “a kind of painting without qualities,” that is to say a body of work with no hierarchy, from which the idea of progress is obviously absent.

The questions that duplication, seen in this way, raises for painting are countless. To those quickly discussed above, let’s add several that address as much the emission as the reception of the canvas, and first and foremost, this boring antiphon: what to paint? Piffaretti, like Opalka, answers: “I paint the painting process.” So be it. But the question of the motif remains, as well as that of the representation, and in the end, of the form that one gives to all that. I gladly contend that duplication resolves half of these questions, but only half. What about this other half that one must “invent”? Within the required minimum, Piffaretti displays some treasures of subtlety, and, it must be said, of know-how, when even though the reiteration constitutes, in itself, an attempt at mastery.

Within an abstraction that flirts with several recognizable signs (however attenuated) of the visible world (a head, clouds, rain, houses, etc.), the artist, like other great painters who preceded him, Richter first of all, fills simply and wisely his space: the space of the plane and the suggested space of the layers, the plane of the painting’s depth. He does not choose to use these signs of the visible world in any premeditated way. It happens that one brushstroke might vaguely suggest a recognizable shape. It happens that therefore the artist emphasizes its identification (since it’s there, let’s go). However, it is, once again, the duplication which confirms these figures: a cloud that is repeated is more identifiable than one cloud alone. In the end, Piffaretti is right, he only paints the painting process. The signs of the world are not winks or kinds of caricatures, and in the end, they have no other functions than of rhythm and space. And if the color acquires such importance here, as Bruno Haas shows, it is because Piffaretti operates within a full system of color and not within a logic of color signs (the link to the referent that characterizes representational systems). And if one can speak of gestural organicity (in counterpoint, sometimes, to the orthogonality induced by the vertical separation), it is in the strict economy of the painting, in its frame, in the impact of the brush and the surface that its movement covers over, in the materiality of its constituent elements.

It is for all these reasons that Bernard Piffaretti’s work, in its first half at least, is neither abstract nor figurative, neither geometric nor gestural. As can be seen in an older painting(4), it is firmly located in this “neither nor” that, in doubling the negations, continues to produce affirmation, better yet, revendication. As for the second half, obviously, it is repainted with the motif (painting the painting process, once again, all over the field, as they say in soccer).

Because here, as in all painting that recoils from encoding or secrets, everything is out in the open. (Piffaretti always plays above-board, and it is in this sense that he can say that his painting is not elitist), the viewer is invited to make a straightforward reading. On only one point could he be accused of the slightest deception, but in this he errs on the side of vigilance. In the majority of the works (except the clearly horizontal paintings), the vertical division of the canvas makes these almost-squares appear like rectangles. No landscape, as has been written, however the window is there, and in this sense, on could interpret the Inacheves [Unfinished works] to be half-open windows. The emptiness that is unveiled there (an emptiness without which the painting would not hold together) shows that the painting, in Piffaretti’s work, is not “a window open onto the world,” but rather a surface devoted solely to exercises of the eye and of the mind, an object to which one adds the tool of its visualization. In that, the Inacheves could be considered paradoxically, as the most finished of his paintings. They open (half-way) onto this absence that is a monochrome (or more precisely an achrome) but which is also the memory of the smooth sex that Duchamp unveiled to the voyeuristic eye (Etant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage), this sex that opened up modernity in the same way as L’Origine du monde [The Origin of the World] closed down the old idea of the painting as a window.

Translated by Jane McDonald

1) Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in 15th century Italy, Oxford University Press, 1972. Gallimard, Paris, 1985 (French translation)

2) La question du double. École Régionale des Beaux-Arts du Mans, 1996

3) Exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Charleroi, 2001

4) Sans Titre [Untitled], 1990. 143 x 114 cm. Collection of the Frac-Bretagne, Châteaugiron

Excerpt from Bernard Piffaretti, 2002

Bernard Piffaretti

French artist Bernard Piffaretti bases his practice on repetition while analysing the components of painting. After art studies at the school of Fine Arts in Saint-Etienne from 1973 to 1979, he began to elaborate his “Piffaretti system”, fixed in 1986. This protocol is at the origin of every work he produces: each is composed of two panels apparently identical, separated by a vertical strip; one of the two parts is an attempt to duplicate the other, made beforehand. Once both panels are finished, the distinction between the copy and the original tends to fade. As the artist admits himself, “the repetition, act by act, on the second half of the canvas, can only produce an imperfect image”: Piffaretti's system aims at showing us this impossible reproduction of the artistic gesture. In some works, the second part is even left irremediably blank, because of the complexity of the shapes painted. Piffaretti also realizes Drawings after paintings, reversing the concept of preparatory sketches and using them to seize his own work.